It was a tense and confusing night after election polls closed in Turkey yesterday, The Guardian’s Constanze Letsch writes. The official result is still unclear, but a runoff between the president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and his main challenger, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, looks increasingly likely. Neither seem to have reached the necessary 50% threshold to win the election outright, but Erdoğan is clearly in the lead. In a press conference in the early morning hours, Kılıçdaroğlu said he that he was confident that he would win the runoff. However, enthusiasm, both onstage and among his supporters, was muted.

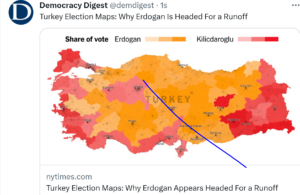

Even so, almost every part of the country shifted against Mr. Erdogan compared with the most recent presidential election in 2018, according to preliminary results, The Times adds:

Even so, almost every part of the country shifted against Mr. Erdogan compared with the most recent presidential election in 2018, according to preliminary results, The Times adds:

Some of the sharpest rebukes came from the provinces around Turkey’s two largest cities, Istanbul and Ankara, where Mr. Erdogan won in 2018 but was behind on Monday, and from areas in central Turkey that have traditionally provided Mr. Erdogan’s core support. …..Voters also leaned away from Mr. Erdogan in the regions hit hardest by the earthquake. Voters there told The Times they were voting for Mr. Kilicdaroglu because of the government’s earthquake response as well as its handling of the economy.

“It is a watershed election,” said former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt. “But democracy is at stake. And my second concern is that we get a result” that means a division of powers — a powerful presidency under Mr. Erdogan and a Turkish Parliament controlled by an unstable opposition coalition. “The risk of constitutional stalemate is quite high,” he added.

Analysts said it would be hard for the opposition to prevail in the runoff, given the first-round results and Erdogan’s considerable election advantages, including his control of state institutions and much of Turkey’s news media, The Post reports. Already, there were signs that his tactics — running a relentlessly negative campaign that tarred the opposition as supporters of “terrorist” groups — had paid dividends.

“It would be hard to see them getting to 50 percent,” said Asli Aydintasbas, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, of the opposition and the second round of voting…The preliminary results appeared to show that Kilicdaroglu’s religious background — as a member of Turkey’s long persecuted Alevi minority, which has beliefs that are distinct from the country’s Sunni Muslim majority — had cut into his support and sparked a sectarian backlash.

“It would be hard to see them getting to 50 percent,” said Asli Aydintasbas, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, of the opposition and the second round of voting…The preliminary results appeared to show that Kilicdaroglu’s religious background — as a member of Turkey’s long persecuted Alevi minority, which has beliefs that are distinct from the country’s Sunni Muslim majority — had cut into his support and sparked a sectarian backlash.

“It seems that in big cities there was a desire for change but across the country, in parts of the Sunni heartlands, there was an unmistakable rejection of an Alevi candidate,” Aydintasbas said. Erdogan, she said, had “consolidated” conservative Sunni Muslims.

Democracy is at stake, says Le Monde.

Andrew Finkel, a founding member and executive board member of the Istanbul-based Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), agrees.

“Democracy and full human rights will not blossom overnight if the current government is booted out of power, but at least it will be a first step on the road to reform,” he told the CPJ. “If they cling on, it will be by their fingertips, which will be [an] incentive to close all channels of dissent and tighten their grip on power.”

“Democracy and full human rights will not blossom overnight if the current government is booted out of power, but at least it will be a first step on the road to reform,” he told the CPJ. “If they cling on, it will be by their fingertips, which will be [an] incentive to close all channels of dissent and tighten their grip on power.”

Whoever wins, it is essential to send “a strong message to judiciary that freedom of expression and media independence are sacred and to be upheld through high-level statements by government officials,” added Finkel, a former Reagan Fascell Democracy Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), and author of Captured News Media: The Case of Turkey, a report from the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA). He also called for an end to “arbitrary restrictions” on internet access.

Captured News Media: The Case of Turkey

The prospect of five more years of Erdogan’s rule will upset civil rights activists campaigning for reforms to undo the damage they say he has done to Turkey’s democracy. Thousands of political prisoners and activists could be released if the opposition prevails, Reuters reports.

“Erdogan has now a clear psychological lead against the opposition,” said Teneo co-president Wolfango Piccoli. “Erdogan will likely double down on his national security focused narratives over the next two weeks.”

Erdogan’s strength is his control over information flow, said Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. In the last half a decade, Erdogan has eliminated autonomy of many of Turkey`s institutions, from courts to foreign ministry to the central bank, with grave ramifications for country`s economy foreign policy, but also electoral boards and media.

90 percent of the media is aligned with them and 80 percent of Turkeys citizens cannot read languages other than Turkish. So you can curate reality, he told PBS NewsHour’s John Yang (above).

Disinformation and stalling the vote count would be part of Erdogan’s toolkit to steal the election, analyst Sinan Ciddi predicted. He detailed the role of chicanery and foul play in “Turkey After Erdogan,” an analysis for the Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

Merve Tahiroglu, Turkey analyst with the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), speculated on the potential for election manipulation by Erdogan and his AK party in a brief for the Heinrich Boll Stiftung.

Merve Tahiroglu, Turkey analyst with the Project on Middle East Democracy (POMED), speculated on the potential for election manipulation by Erdogan and his AK party in a brief for the Heinrich Boll Stiftung.

The election results may have borne out the predictions of one analyst who suggested that the CHP’s Kemalist legacy could act as a drag on the opposition.

The greatest obstacle for the opposition may be the grievance still held by much of the population against the Kemalist hegemony—and against the party, the CHP, that long symbolized it, Philip Balboni wrote for the Journal of Democracy. Kılıçdaroğlu has been signaling a desire to acknowledge and make amends for the CHP’s past wrongs.