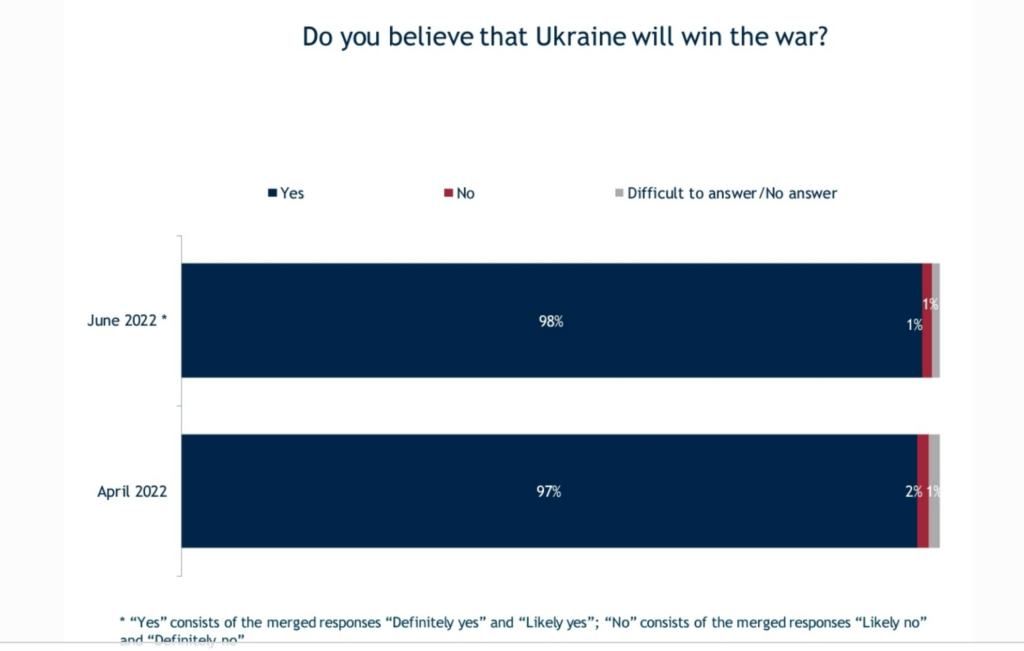

Some 98% of Ukrainians believe their country will definitely or likely win the war against Russia, according to the latest public opinion survey conducted by the International Republican Institute (IRI). East Ukraine is the least optimistic, but even there, 94% think Ukraine will win.

“The information gathered from this poll is confirmation from our previous survey,” said Stephen Nix, Senior Director for IRI’s Eurasia Division. “Ukrainians are very firm in their conviction that they will be victorious in the conflict against Russia, and they overwhelmingly support the actions of their wartime president.”

The survey shows that confidence in winning the war and approval for President Zelensky remain robust. Most Ukrainians do not believe in conceding any territory and support for NATO membership has spiked, Euromaidan reports.

Meduza

The war in Ukraine has undermined the West’s appeasers, yet plenty of Western intellectuals and politicians still ignore what Moscow is saying loud and clear, notes Alexey Kovalev, an investigative editor at Meduza. One of my most revealing interviews was with Polina Kovalevskaya, a refugee from Mariupol, which was already a mass grave by the time she and her family escaped. When I asked them for a photo of their former home, they sent me a video instead, he writes for Foreign Policy:

What makes the video so chilling wasn’t just the fact that targeting civilians is a war crime. It’s that the clip bears the unmistakable logo of RT, the Russian channel that started off in 2005 as a mostly benign attempt to improve Russia’s international image and ended up as a domestic disinformation bullhorn. The video’s unequivocal message: This is what we’re doing in Ukraine, and we’re not even going to pretend anything else.

Putin has clearly identified democracy as an existential threat and framing the conflict in this way has strengths that realist John Mearsheimer’s focus on supposedly aggressive NATO enlargement* lacks, argues Erik Jones, Director of the European University Institute’s Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies:

Putin has clearly identified democracy as an existential threat and framing the conflict in this way has strengths that realist John Mearsheimer’s focus on supposedly aggressive NATO enlargement* lacks, argues Erik Jones, Director of the European University Institute’s Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies:

- To begin with, it builds on consistent features that stretch across Russian behavior both at home and abroad. The brutal military tactics deployed in Ukraine were first tested in Chechnya and then perfected in Syria — neither of which was ever in danger of being included in the Atlantic Alliance. The suppression of journalists and the forced movement of populations have been done at home and abroad as well. So has the co-option of oligarchs where that is possible and the expropriation of their assets where it is not.

- A second strength is that it makes it easier to understand Russia’s on-again, off-again partnership with NATO. ….There were moments of high tension, like when the Russian military occupied Pristina airport in June 1999, but that did not stop the cooperation altogether. This pattern is hard to reconcile with NATO as an existential threat, but easier when NATO is simply an instrument to achieve various objectives.

A third strength is that the threats posed by political opposition and democratisation are even more credible than any legacy concerns that Russia might have about the NATO alliance. … The United States also engaged in regime change in Iraq, with a coalition of the willing, and in Afghanistan, bringing NATO allies in for support after the fact. …But this is where the qualifications end. Neither the United States nor NATO has never moved openly against a nuclear power. …Meanwhile, political oppositions and pro-democracy movements have overthrown large numbers of authoritarian regimes, including in the Soviet Union, which was one of only two nuclear superpowers. If anything, new technologies have strengthened the ability of such groups to challenge political authority. The results have not always been positive for those who initiate the revolution, but they have almost always been ‘existential’ for the regime that is overthrown.

A third strength is that the threats posed by political opposition and democratisation are even more credible than any legacy concerns that Russia might have about the NATO alliance. … The United States also engaged in regime change in Iraq, with a coalition of the willing, and in Afghanistan, bringing NATO allies in for support after the fact. …But this is where the qualifications end. Neither the United States nor NATO has never moved openly against a nuclear power. …Meanwhile, political oppositions and pro-democracy movements have overthrown large numbers of authoritarian regimes, including in the Soviet Union, which was one of only two nuclear superpowers. If anything, new technologies have strengthened the ability of such groups to challenge political authority. The results have not always been positive for those who initiate the revolution, but they have almost always been ‘existential’ for the regime that is overthrown. A fourth strength of this alternative framing is that it explains why we should all learn more about what Putin and his allies are saying about Russian history, its society, its people, and their future. Because if democracy and political opposition are the government’s most important existential threats, then that country’s political leadership needs some alternative formula to legitimate their authority. Nationalism is an obvious candidate, because it is a political project to empower the people to act through the state. But that abstract formulation tells us very little about how nationalism works in the Russian context to strengthen and build support around Vladimir Putin’s regime in its battle against representative democracy, free and fair elections, free speech and assembly, and those other values promoted by the West.

A fourth strength of this alternative framing is that it explains why we should all learn more about what Putin and his allies are saying about Russian history, its society, its people, and their future. Because if democracy and political opposition are the government’s most important existential threats, then that country’s political leadership needs some alternative formula to legitimate their authority. Nationalism is an obvious candidate, because it is a political project to empower the people to act through the state. But that abstract formulation tells us very little about how nationalism works in the Russian context to strengthen and build support around Vladimir Putin’s regime in its battle against representative democracy, free and fair elections, free speech and assembly, and those other values promoted by the West.

Rather than rejecting outright any claim that Russia has imperial ambitions, this alternative framing of the existential threat as coming from democracy and not NATO forces us to ask what ambitions Putin has to offer to the people who support him and his allies, he writes for Encompass.

I t’s is worth examining other factors that might be motivating the Russian president and his advisors, adds Newcastle University’s One of these was neatly summed up by historian Serhii Plokhy in his 2018 study, Lost Kingdom, A History of Russian Nationalism from Ivan the Great to Vladimir Putin, he writes for The Conversation:

t’s is worth examining other factors that might be motivating the Russian president and his advisors, adds Newcastle University’s One of these was neatly summed up by historian Serhii Plokhy in his 2018 study, Lost Kingdom, A History of Russian Nationalism from Ivan the Great to Vladimir Putin, he writes for The Conversation:

Russia today has enormous difficulty in reconciling the mental maps of Russian ethnicity, culture, and identity with the political map of Russian Federation.

Ukraine’s resilient response to Russian aggression highlights the country’s commitment to democratic values and active citizen participation, adds Mehri Druckman, IREX’s Country Director for Ukraine and Chief of Party for the USAID-funded Ukraine National Identity Through Youth (UNITY) program. As the war rages around them, young Ukrainians are also volunteering in large numbers to distribute humanitarian aid through digital platforms like SpivDiia that match people’s needs with resources from businesses and private individuals, she writes for the Atlantic Council.

Russian strategy toward Ukraine is designed to demoralize and demotivate, notes Anne Applebaum. But it encounters a potent countervailing force in the form of activists and volonteri in groups like Anna Bondarenko‘s Ukrainian Volunteer Service (UVS) and Mikhail Reva’s Reva Foundation, which has drawn not just on Ukrainian civil society to support the Ukrainian army, but civil society in many countries, she writes for The Atlantic.

*Democratic enlargement, not NATO expansion, was always the key for Putin, says Stanford University’s Michael McFaul (below).