Remarks – Nadia Diuk – Ukraine’s Convoluted Transition from National Endowment for Democracy on Vimeo.

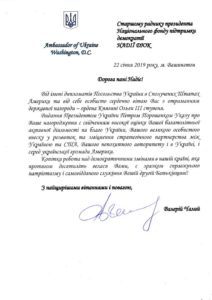

Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko has honored Nadia Diuk (above), Senior Advisor at the National Endowment for Democracy, with the Order of Princess Olga (III degree) in recognition of her lifetime’s commitment to advancing the country’s democracy and civil society.

For over twenty years prior to her appointment as Vice President, she supervised NED programs in Europe and Eurasia where she worked on programs and strategies for the underground democratic movements before 1989, through to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and beyond. Her publications include two co-authored books The Hidden Nations: The People Challenge the Soviet Union and New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence and the recently published The Next Generation in Russia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan: Youth, Politics, Identity and Change.

For over twenty years prior to her appointment as Vice President, she supervised NED programs in Europe and Eurasia where she worked on programs and strategies for the underground democratic movements before 1989, through to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, and beyond. Her publications include two co-authored books The Hidden Nations: The People Challenge the Soviet Union and New Nations Rising: The Fall of the Soviets and the Challenge of Independence and the recently published The Next Generation in Russia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan: Youth, Politics, Identity and Change.

“As the largest of the non-Russian republics, Ukraine has always been a bellwether of sorts,” she wrote for The Journal of Democracy in 2001, ten years after the Soviet collapse.

Its success at handling three simultaneous “revolutions” – consolidating statehood, reforming the economy, and establishing democracy – and posing a counterweight to Moscow has been crucial in preventing the resurgence of Russia as an imperial power. Ukraine presents a mixed picture of achievements and setbacks, she added – an observation as true now as it was then.

Does the West really need Ukraine? How to overcome “Ukraine fatigue”? And what should the West demand from Ukrainian authorities in 2019 in exchange for further support? analyst Valerii Pekar writes for New Eastern Europe.

Does the West really need Ukraine? How to overcome “Ukraine fatigue”? And what should the West demand from Ukrainian authorities in 2019 in exchange for further support? analyst Valerii Pekar writes for New Eastern Europe.

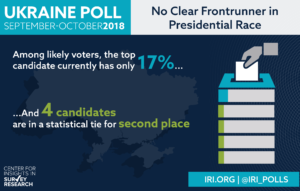

Actually, there are two drivers of reforms in Ukraine, namely the active minority of Ukrainians involved in civil society organizations on the one hand, and Western governments and international financial organizations on the other hand. The majority of Ukrainian NGOs represent Ukrainians with civil responsibility, liberal values, and often better education. Now unfortunately, five years after the Revolution of Dignity (December 2013 — February 2014), this active minority has no political representation. There are many reasons why a viable liberal political party was not established, including objective factors like long period of statelessness and weakness of political culture, almost total absence of modern political parties in a climate where all entities are old-fashioned patron-client clans, high entry barriers and lack of resources like media (owned by oligarchs) which are necessary to create a nation-wide structure, and so on.

Realist critics of “liberal hegemony” like Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer deem even notable examples of pragmatic and non-ideological American restraint as too interventionist, notes Michael Fitzsimmons, Visiting Research Professor at the Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. Presidents Bush and Obama were harshly criticized for not exerting more American power in response to conflicts in Georgia, Syria, and Ukraine. But for Walt and Mearsheimer, at least, their responses are, somehow, simply more examples of misguided activism, he writes for The American Interest:

Realist critics of “liberal hegemony” like Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer deem even notable examples of pragmatic and non-ideological American restraint as too interventionist, notes Michael Fitzsimmons, Visiting Research Professor at the Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College. Presidents Bush and Obama were harshly criticized for not exerting more American power in response to conflicts in Georgia, Syria, and Ukraine. But for Walt and Mearsheimer, at least, their responses are, somehow, simply more examples of misguided activism, he writes for The American Interest:

Mearsheimer goes so far as to say that, “The United States and its European allies are mainly responsible for the crisis” prevailing there since 2014. The logic appears to be that Moscow cares a lot about its influence over Ukraine, while Ukraine is peripheral to U.S. vital interests; therefore Ukrainian interests ought to be irrelevant to the United States. This is a defensible but debatable premise. To infer from it that the United States and Europe are primarily to blame for the current troubles in Ukraine requires an extraordinarily narrow interpretation of the region’s history and politics.