After the collapse of the Soviet Union, NATO membership was often seen as a path toward EU integration among the new democracies of central and eastern Europe. But since NATO membership does not appear to be on the near-term horizon for Kyiv, the model should be reversed: the EU should explore opening the door to Ukrainian membership, say Alina Polyakova and Daniel Fried.

The United States is long overdue to rethink its Russia strategy. Successive attempts to reframe relations have been tried and found wanting. Putin’s aggression has brought this on. Washington’s task is to see that Putin fails and that the West’s democratic alternative—based on a rules-based, liberal world order—prevails, they write for Foreign Affairs.

The narrative of Russian backlash against NATO expansion has become a dominant framework for explaining—if not justifying—Moscow’s ongoing war against Ukraine. But this argument has two flaws, one about history and one about Putin’s thinking, Robert Person and Michael McFaul write for the Journal of Democracy:

The narrative of Russian backlash against NATO expansion has become a dominant framework for explaining—if not justifying—Moscow’s ongoing war against Ukraine. But this argument has two flaws, one about history and one about Putin’s thinking, Robert Person and Michael McFaul write for the Journal of Democracy:

- First, NATO expansion has not been a constant source of tension between Russia and the West, but a variable. Over the last thirty years, the salience of the issue has risen and fallen not primarily because of the waves of NATO expansion, but due instead to waves of democratic expansion in Eurasia. In a very clear pattern, Moscow’s complaints about NATO spike after democratic breakthroughs. …

- This reality highlights the second flaw: Because the primary threat to Putin and his autocratic regime is democracy, not NATO, that perceived threat would not magically disappear with a moratorium on NATO expansion. Putin would not stop seeking to undermine democracy and sovereignty in Ukraine, Georgia, or the region as whole if NATO stopped expanding.

Credit: Stanford CREEES

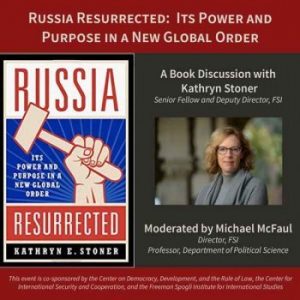

Let’s remember what Europe looked like before NATO, as opposed to the way it looks now, adds Kathryn Stoner, Mosbacher Director of Stanford University’s Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law and author of Russia Resurrected: Its Power and Purpose in a New Global Order. It was a region pockmarked by clashes between empires claiming spheres of influence; and when these God-given imperial borders were perforated, there followed decades of war. The post-World War II and post-Cold War orders were systems built in reaction to this horrific history and, therefore, grounded not on the idea of empire but on respect for state sovereignty, she writes for American Purpose.

Ukraine’s civil society leaders* declared that the country had reached “a point of no return” and appealed to the US and EU for the “severest sanctions” to halt Russia’s invasion.

Journal of Democracy contributor Prof. Taras Kuzio (Henry Jackson Society and Kyiv Mohyla Academy) talks about the Russia-Ukraine crisis, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the conflict in Donbass, and Ukraine’s membership in NATO and the EU (above).

The National Endowment for Democracy (NED) has been a proud partner of Ukraine’s civil society groups, media outlets, and human rights defenders since 1989—before the Ukrainian people declared independence in 1991—as they have confronted enormous challenges in building an independent and free country, it said in a statement of solidarity with Ukraine.

“Vladimir Putin fears the agency of Ukrainian citizens to determine their own future and the example that sets for Russia,” said NED President and Chief Executive Officer Damon Wilson. “This crisis has profound consequences for the cause of freedom and democracy in the region and around the world today. Now is the time for free people around the world to rally in support of a free Ukraine.”

“Vladimir Putin fears the agency of Ukrainian citizens to determine their own future and the example that sets for Russia,” said NED President and Chief Executive Officer Damon Wilson. “This crisis has profound consequences for the cause of freedom and democracy in the region and around the world today. Now is the time for free people around the world to rally in support of a free Ukraine.”

There are no Chamberlains in this story, but no Churchills either, Anne Applebaum writes for The Atlantic. Despite everything that was said [at the Munich Security Conference], everything that was promised, and everything that was discussed, Ukraine will fight alone.

Besides isolating Russian state-owned banks, the escalatory sanctions that U.S. officials have prepared would cut off the ability to purchase critical technologies from American companies, The New York Times reports.

If the United States imposes the harshest penalties, “there will be unexpected and unpredictable consequences for global markets,” said Maria Snegovaya, a visiting scholar at George Washington University [and former NED Penn Kemble fellow] who co-wrote an Atlantic Council paper on U.S. sanctions on Russia.

Former NED board member Francis Fukuyama

Putin is seeking “to undermine the belief of Western democracies in their own systems, but he’s actually not trying to pretend that Russia has a superior system that would apply in other countries,” said Stanford’s Francis Fukuyama. The ideological battles of the Cold War have been replaced by more traditional geopolitical competition, he tells The New Yorker’s Robin Wright.

“Russia is simply trying to gain influence using the sort of limited military leverage that it has in different parts of the world. But that’s not the Cold War,” Fukuyama said. Russia today is far weaker than the Soviet empire was, especially as much of Eastern Europe is “pretty solidly aligned with the West.”

The Revolution on Granite of 1990, the Orange Revolution of 2004 and the Revolution of Dignity of 2013-14 continued Ukraine’s breakaway from its Soviet, colonial past, says Kyiv-based rule of law expert Artem Shaipov. Each of these revolutions taught Ukrainians valuable lessons as to the role of civil society in nation building, setting a popular vision of the future and holding the government to account.

Putin’s distorted narrative on Ukraine is a chastening reminder of the pernicious prevalence of autocratic discourses and the democratic imperative to refute them, but significant segments of political leadership in Central and Eastern Europe remain ignorant about authoritarian influence operations, according to Drivers of Narratives Undermining Democracy & Transatlantic Unity, a new NED-funded report from the GLOBSEC Policy Institute.

Putin’s distorted narrative on Ukraine is a chastening reminder of the pernicious prevalence of autocratic discourses and the democratic imperative to refute them, but significant segments of political leadership in Central and Eastern Europe remain ignorant about authoritarian influence operations, according to Drivers of Narratives Undermining Democracy & Transatlantic Unity, a new NED-funded report from the GLOBSEC Policy Institute.

Compared to Serbia in 2000 or Georgia in 2003, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004 was a much larger threat to Putin, Person and McFaul add in the Journal of Democracy:

- First, the Orange Revolution occurred suddenly and in a much bigger and more strategic country on Russia’s border. The abrupt pivot to the West by Yushchenko and his allies left Putin facing the prospect that he had “lost” a country on which he placed tremendous symbolic and strategic importance….

- Second, those Ukrainians who rose up in defense of their freedom were, in Putin’s own assessment, Slavic brethren with close historical, religious, and cultural ties to Russia. If it could happen in Kyiv, why not in Moscow? Several years later, it almost did happen in Russia when a series of mass protests erupted in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other cities in the wake of fraudulent parliamentary elections in December 2011.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine should trigger a crisis of European identity, argues Brookings analyst William A. Galston. If force is a permanent feature of international relations, the European Union must either take more responsibility for its own defense or admit that it has subcontracted this job to the U.S. indefinitely, along with some of the EU’s strategic independence, he writes for The Wall Street Journal.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine should trigger a crisis of European identity, argues Brookings analyst William A. Galston. If force is a permanent feature of international relations, the European Union must either take more responsibility for its own defense or admit that it has subcontracted this job to the U.S. indefinitely, along with some of the EU’s strategic independence, he writes for The Wall Street Journal.

This is no time for hesitation. President Biden must lead without ambivalence, and members of the Western alliance must endure short-term discomfort to protect democracy’s future. The alternative is a repetition of 1938, former NED board member Galston insists.

Indeed….

There should be no illusions about Putin’s long-term strategic goal of stopping democratic expansion, in Ukraine and the rest of the region, Person and McFaul conclude in the Journal of Democracy.

There should be no illusions about Putin’s long-term strategic goal of stopping democratic expansion, in Ukraine & the rest of the region: @McFaul & @RTPerson3 refute Putin’s distorted rationale via @ThinkDemocracy‘s @JoDemocracy https://t.co/7fYyBzjRLo

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) February 23, 2022

*Signatories included:

- Hanna Hopko, Democracy in Action Initiative, Head of the Foreign Affairs Committee (2014-2019)

- Daria Kalenyuk, Olena Halushka, AntiCorruption Action Center

- Ostap Yednak, Maksym Kyiak, Natalya Veselova, Maria Golub, ANTS Network

- Olena Kravchenko, Environment-People-Law, International Law Organization

- Olga Aivazovka, Civil Network “OPORA”

- Oleksandra Matviychuk, Center for Civil Liberties

- Mykhailo Gonchar, CGS Strategy XXI

- Josef Zissels, co-president of Vaad of Ukraine, member of the Initiative group “First of December”

- Mykhailo Ratushnyi head of Ukrainian World Coordinating Council

- Oleksii Mushak, Member of Parliament (2014-2019), Adviser to Prime-Minister (2019-2020)

- Sergiy Parkhomenko, Head of center of Foreign Policy Studies OPAD

- Andriy Teteruk, Veteran of Russian war against Ukraine, Member of Parliament (2014-2019)

- Ihor Lapin, Ukrainian War veteran, Member of Parliament (2014-2019)

- Alya Shandra, editor in chief, Euromaidan Press

- Myroslav Hai, human rights activist, Russian-Ukrainian war veteran,

- Agiya Zagrebelska, President of Foundation Mir&Co, co-founder League Antitrust