In less than a month, Juan Guaido has gone from a virtual unknown in Venezuelan politics to the country’s most-watched figure, assuming the presidency of the opposition-controlled congress and briefly being detained by the secret police, Reuters reports:

On Wednesday, the skinny 35-year-old from the South American country’s hardscrabble Caribbean coast thrust himself onto the international stage with the boldest challenge to socialist President Nicolas Maduro’s rule in years: he declared himself interim president, a move swiftly recognised by the United States, Canada and many Latin American countries.

What this will come down is whether the momentum being created today creates the necessary fissures in the military so that Maduro loses that critical base of support,” Jason Marczak, an expert on Latin America with the Atlantic Council, told Foreign Policy.

“There is no doubt that the behavior of guys with guns will define much of what will happen in the coming days and shape politics in Venezuela,” Moises Naim, a former Venezuelan minister now at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told a Davos panel session on Thursday. A former National Endowment for Democracy board member, Naim described Venezuela as a “criminalized country,” rife with local and transnational gangs “maybe even more lethal and more dangerous” than the military.

David Smilde, a Venezuela expert at Tulane University in the US, said the decision by the US, Canada and others to recognise Mr Guaidó had serious practical implications for the Maduro government and were less symbolic than first appeared. “It could lead courts in the US and elsewhere to give control to Venezuela’s foreign assets to the [opposition-dominated] National Assembly instead of the Maduro government,” he told the FT.

Guaidó is a protégé of one of the opposition’s most prominent leaders, Leopoldo López, who was jailed in 2014, Quartz reports. “He’s a hard worker, he’s humble, and he can unite us,” López’s wife, activist Lilian Tintori [who received the National Endowment for Democracy]‘s 2015 Democracy Award on his behalf], told the New York Times about Guaidó. “But the risk for him is enormous. They may do the same to Juan as they did to Leopoldo, to put him in jail.”

Guaidó is a protégé of one of the opposition’s most prominent leaders, Leopoldo López, who was jailed in 2014, Quartz reports. “He’s a hard worker, he’s humble, and he can unite us,” López’s wife, activist Lilian Tintori [who received the National Endowment for Democracy]‘s 2015 Democracy Award on his behalf], told the New York Times about Guaidó. “But the risk for him is enormous. They may do the same to Juan as they did to Leopoldo, to put him in jail.”

The decision by Washington to defy Maduro and keep U.S. Embassy staff in Caracas effectively turned them into pawns in what is now an unpredictable international crisis, the Washington Post reports.

“This highlights the enormous risks of having parallel governments,” said Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue. “The situation has put the U.S. and the embassy staff in a very difficult position. If the diplomats do not leave, they could face considerable danger. Yes, it could get ugly. And yet, if they do leave, that would deflate Guaidó.”

The Lima Group, which has been vocal in denouncing Maduro, said it supported beginning the process of a democratic transition following its constitution with aim of carrying out new elections as soon as possible. The statement was signed by Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay and Peru. Mexico was the only member to not sign, the Post adds.

The nonprofit Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict registered protests in 70 neighborhoods, all of which were met with tear gas and rubber bullets, the Post adds.

The nonprofit Venezuelan Observatory of Social Conflict registered protests in 70 neighborhoods, all of which were met with tear gas and rubber bullets, the Post adds.

Venezuela has seen protests like these many times before, but this week’s are different. For years, such protests were concentrated in middle-class enclaves in Caracas and other big cities. Working-class people stayed well away from them, allowing the self-described socialist government to portray the protests as a kind of middle-class tantrum over lost privileges, analyst Francesco Toro writes for the Post:

This week, though, nighttime protests lit up working-class areas throughout Caracas’s most reliably pro-government areas — while middle-class protest hot spots were quiet. On Monday and Tuesday night, though, the focus of protests shifted from the impoverished parents of better-educated migrants to Venezuela’s now desperate working class. After a small attempted rebellion by a couple of dozen of National Guard troops failed, nighttime pot-banging protests began to break out all over Caracas, and small groups of protesters spilled out onto street corners, setting piles of garbage on fire and manning makeshift barricades.

Discontent has deepened across Venezuela’s socioeconomic classes as hyperinflation has rendered wages virtually worthless. the New York Times adds:

Discontent has deepened across Venezuela’s socioeconomic classes as hyperinflation has rendered wages virtually worthless. the New York Times adds:

Citizens of what was once one of the region’s wealthiest nations, endowed with plentiful oil, have starved to death and died from preventable diseases. More than three million Venezuelans have left the country in recent years, and those who stayed have struggled to find food and medicine while contending with water shortages and rampant crime.

Even the most ardent of Chavista cheerleaders and fellow-travelers appear to recognize the regime’s bankruptcy.

Eva Golinger, an American lawyer who was a close friend of the leftist strongman Hugo Chávez, Mr. Maduro’s mentor and predecessor, said the government could no longer count on its traditional bastions of support to overpower opposition movements, which in the past were led by wealthy and middle-class Venezuelans, The Times observes.

“The difference this time is that the discontent is not just opposition,” said Ms. Golinger, who wrote a memoir called “Confidante of ‘Tyrants,’ ” about her ties with Venezuelan and other leaders. “In fact, it’s mainly poor people who are tired of going without basic products and earning decent wages.”

“The difference this time is that the discontent is not just opposition,” said Ms. Golinger, who wrote a memoir called “Confidante of ‘Tyrants,’ ” about her ties with Venezuelan and other leaders. “In fact, it’s mainly poor people who are tired of going without basic products and earning decent wages.”

Maduro has become more autocratic and governed increasingly erratically since taking office in 2013 as Hugo Chávez’s successor. His re-election as president in May 2018 – when Maduro won 68 percent of the vote despite having an approval rating of just 21 percent – was widely declared fraudulent, writes Global Affairs Editor for The Conversation US.

“The ruling Socialist Party used all the power of its increasingly authoritarian regime to tip the May 2018 election in Maduro’s favor,” notes Miguel Angel Latouche, a professor at the Central University of Venezuela. “For months, the regime coerced citizens to register as Socialist Party members, traded food for votes and blacklisted opposition candidates,” he adds. The government also called the elections several months early, preventing the opposition from organizing successful campaigns.

“Fewer than half of Venezuela’s registered voters participated in the South American country’s May 2018 election, punishing a government they don’t support by simply not voting,” says Latouche.

“Fewer than half of Venezuela’s registered voters participated in the South American country’s May 2018 election, punishing a government they don’t support by simply not voting,” says Latouche.

Though intimidation has worked for the government in the past, it may not this time, said Dimitris Pantoulas, a Caracas-based political analyst. Discontent now appears to be more widespread and the ranks of security forces and government-allied groups have been thinned by the mass exodus of mostly young Venezuelans, he said.

“The government is resorting to its old tricks, but the people no longer believe them,” Pantoulas told AP.

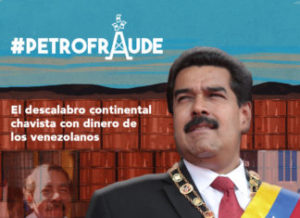

The regime’s endemic corruption was exposed this week as “Petrofraude” (above and right) by a civil society consortium. Venezuela negotiated energy agreements with 14 countries for the delivery of millions of barrels of oil in in a fraudulent system of overpricing and false deliveries in order to secure diplomatic allies at the expense of citizens’ welfare, an investigation reveals.

The regime’s endemic corruption was exposed this week as “Petrofraude” (above and right) by a civil society consortium. Venezuela negotiated energy agreements with 14 countries for the delivery of millions of barrels of oil in in a fraudulent system of overpricing and false deliveries in order to secure diplomatic allies at the expense of citizens’ welfare, an investigation reveals.

For others across the region flaunting international commitments and the rights of their peoples under their own democratic frameworks, such as the Ortega dictatorship in Nicaragua the lesson is clear, says Evan Ellis, a non-resident senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C; democracy, human rights, and constitutional commitments matter, and the region can be respectful of sovereignty and slow to intervention yet still use its collective legal and diplomatic authority to bring justice to those who transgress the rights of and commitments to their own people.

It’s tempting to think the U.S. should send in troops, a la Panama in 1989, to assist the rebellion, the Wall Street Journal adds. But Venezuelans have to win their freedom themselves, and if they do they are likely to prize it all the more.

Venezuelans seem to think so too.

Connectas

According to a Datanálisis survey, 63 percent support “a negotiated settlement to remove President Maduro from power.”

Eric Farnsworth, a former State Department official and now vice president of the Council of the Americas in Washington, said that this week’s decision is partly due to Senator Marco Rubio’s work from the early days of the Trump administration, the Miami Herald adds:

Farnsworth recalled that Rubio got Trump to meet with Venezuelan activist Lilian  Tintori [right], the wife of imprisoned Venezuelan politician Leopoldo López. “I think he’s been effective, if you judge effective by getting the administration in the direction [Rubio’s] been urging,” Farnsworth said. He noted that Rubio’s constant and public push for additional actions in Venezuela through potentially wide-ranging oil sanctions and the designation of the country as a state sponsor of terrorism gives the

Tintori [right], the wife of imprisoned Venezuelan politician Leopoldo López. “I think he’s been effective, if you judge effective by getting the administration in the direction [Rubio’s] been urging,” Farnsworth said. He noted that Rubio’s constant and public push for additional actions in Venezuela through potentially wide-ranging oil sanctions and the designation of the country as a state sponsor of terrorism gives the  Trump administration political space to take action.

Trump administration political space to take action.

“By being very vocal about actions that you would like to see, it creates political space for action to be seen as timely,” Farnsworth said. “We can argue about specific things he’s recommending, but by taking a high-profile position, he’s causing other people to react and move.”

Militarized narco-dictatorship

The Vatican has failed to deploy its moral capital in an effort to resolve the country’s crisis, notes George Weigel, Distinguished Senior Fellow of Washington, D.C.’s Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he holds the William E. Simon Chair in Catholic Studies.

In a January 6 letter to their fellow Latin American Pope Francis, 20 former Latin American heads of state and government, including Nobel Peace Prize winner Oscar Arias of Costa Rica, reminded the pope that Venezuelans “are victims of oppression by a militarized narco-dictatorship which has no qualms about systematically violating the rights to life, liberty, and personal integrity,” a corrupt regime that has also “subjected [Venezuelans] to widespread famine and lack of medicine,” he writes for First Things.

In these contexts, the former leaders concluded, the papal “call for harmony….can be understood by the victimized nations [as an instruction] that they should come to agreement with their victimizers.” Which is why the majority in Nicaragua and Venezuela received the pope’s Christmas message “in a very negative way.”

Revolution in Ruins: The Hugo Chávez Story (BBC Two – below) is a dense and deeply depressing precis of his 14-year rule of Venezuela: a country with the largest proven oil reserves on the planet where 90% of the population live in poverty, the Guardian adds.