The recent suicide bombings in Surabaya, Indonesia highlight the country’s continued struggle with radicalism and terrorism. Claimed by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), these attacks typify the latest chapter in Indonesia’s decades-long struggle with violent extremism, notes the International Republican Institute:

Since the fall of the dictatorial Suharto regime in 1998, terrorism, ethno-religious conflict and intolerance have undermined the country’s democratic progress. Focus group data by IRI’s Center for Insights in Survey Research reveals some of the key vulnerabilities to violent extremism in Indonesia’s West Java province, as well as sources of resilience to radical ideology.

Indonesia’s authorities are conducting an ineffective fight against the radical Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir (HTI), analysts Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat and Diwangkara Bagus Nugraha write for the International Policy Digest:

Indonesia’s authorities are conducting an ineffective fight against the radical Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir (HTI), analysts Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat and Diwangkara Bagus Nugraha write for the International Policy Digest:

While organisations such as HTI carry out their campaigns through various civil society institutions such as the mainstream media, the Internet, academic institutions and places of worships, the government’s counter efforts must also be carried out in the same way. For example, it could promote the idea that the country’s own ideologies are the most suitable to be applied through the mass media or by incorporating certain subjects in the national curriculum to be taught at schools or universities.

The IRI Indonesia survey’s findings highlight several potential sources of vulnerability to violent extremism:

- Finding #1: Most participants from across the focus groups were critical of the quality of Indonesia’s democracy, often citing elitism, the importance of moneyed interests and growing intolerance. Participants from Islamic political parties were particularly disillusioned with democratic outcomes.

- Finding #2: Most participants were critical of the Indonesian government’s performance on specific issues, including corruption, insecurity, economic hardship and its defense of free expression. However, members of the nationalist parties, which control government, were less critical of the government and its overall representation of constituents and ability to address the country’s primary challenges.

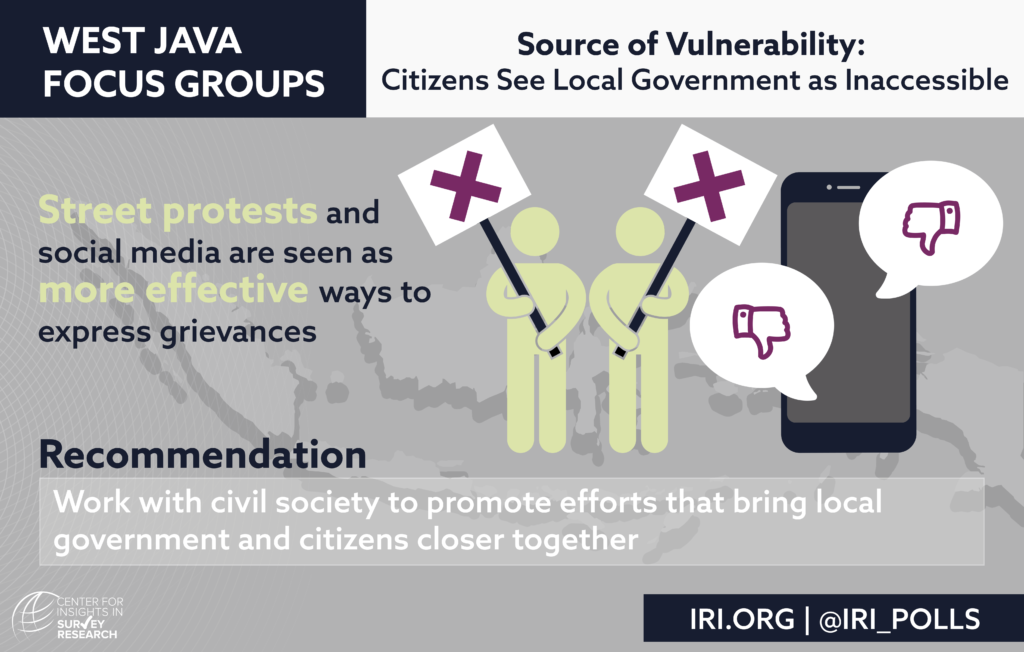

- Finding #3: Most participants find local government inaccessible, with many saying social media and street protests are more effective forums for expressing grievances.

- Finding #4: Many participants cited Islam as a justification for their opposition to minorities and the prospect of women being elected president.

- Finding #5: Participants were closely divided on whether the government should be more Islamic, with proponents often citing Islam’s orientation toward justice and morality.

The survey’s findings also highlight several potential sources of resilience to violent extremism, notes IRI, a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy:

The survey’s findings also highlight several potential sources of resilience to violent extremism, notes IRI, a core institute of the National Endowment for Democracy:

- Finding #1: Most participants across the focus groups expressed a common definition of democracy and had positive associations with the nation’s founder, Sukarno, and his ideology, Pancasila.

- Finding #2: Most participants were opposed to violence in all cases and associated the Islamic State (ISIS) and Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) with negative characteristics. However, a small group of participants believed violence can be justified when defending Islam or a political position.

- Finding #3: Most participants described the drivers of violent extremism in negative terms, often citing a lack of education and opportunity.

- Finding #4: Participants from religiously conservative parties, Islamic organizations, and university groups expressed some support for minority religious groups despite opposing other inclusive policies and political behavior.