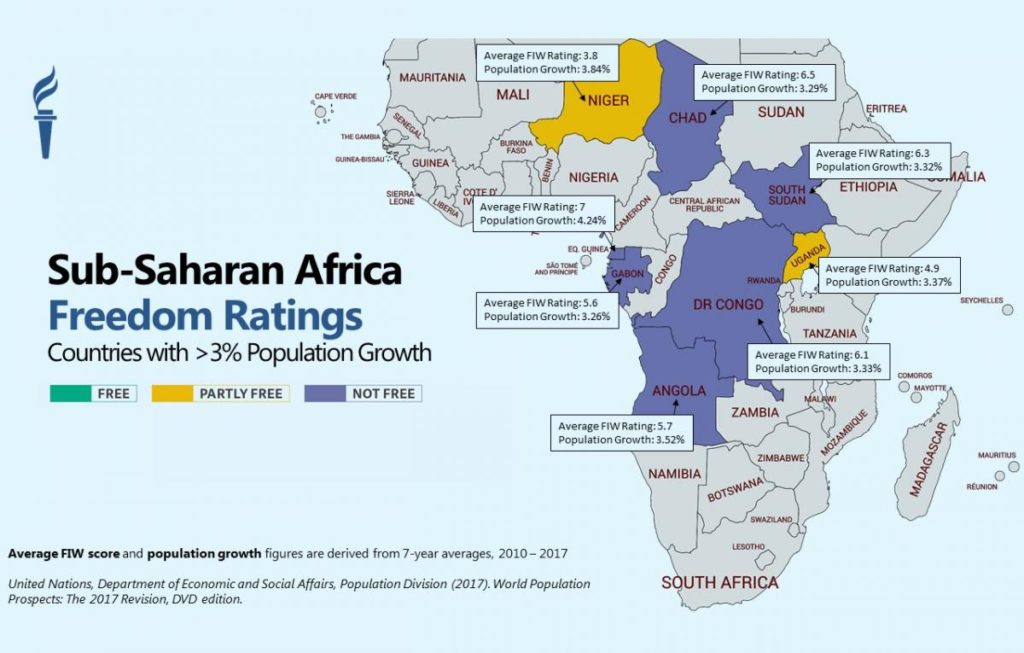

In the 60-plus years since the countries of sub-Saharan Africa started becoming independent, democracy there has advanced unevenly. Even as some countries in the region have grown into success stories, most have failed to embrace true democracy, despite a deep hunger for it among their populations. Today, a mere 11 percent of Africans live in countries that Freedom House considers free, note analysts Judd Devermont and Jon Temin.

But change is afoot. Whereas from 2010 to 2014, the region experienced nine transfers of power from one leader to another, since 2015, the region has experienced 26 of them, they write for Foreign Affairs:

Afrobarometer

Some of these transitions amounted to one leader relinquishing his or her seat to a handpicked successor, but more than half featured an opposition candidate defeating a member of the incumbent party. Of the 49 leaders in power in sub-Saharan Africa at the beginning of 2015, only 22 of them remained in power as of May 2019. …….Africa’s new set of leaders includes former military dictators turned democrats, party loyalists who steadily moved up the ranks, and a few political outsiders, among them a disc jockey, a business magnate, and a former soccer star. Five of them will prove especially pivotal: Abiy Ahmed of Ethiopia, João Lourenço of Angola, Cyril Ramaphosa of South Africa, Félix Tshisekedi of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria.

“These leaders preside over countries that make up nearly half the population of sub-Saharan Africa, include four of the region’s five largest economies, and have some of the continent’s strongest militaries,” they add. “And all of them claim to reject the corruption and misrule associated with their predecessors.”

Warlord democrats?

Since the early 1990s, post-civil war democratization has become the ‘go-to’ mechanism for resolving internal armed conflicts, note analysts Fofana Abraham, Henrik Persson, and Anders Themnér. In an African context, this has resulted in the rise of so-called warlord democrats (WDs) – the former military and political leaders of armed groups, who now take part in national elections, they write in Yesterday warlord, today presidential candidate: Ex-military leaders running for office in post-civil war societies, a report from The Nordic Africa Institute.

Since the early 1990s, post-civil war democratization has become the ‘go-to’ mechanism for resolving internal armed conflicts, note analysts Fofana Abraham, Henrik Persson, and Anders Themnér. In an African context, this has resulted in the rise of so-called warlord democrats (WDs) – the former military and political leaders of armed groups, who now take part in national elections, they write in Yesterday warlord, today presidential candidate: Ex-military leaders running for office in post-civil war societies, a report from The Nordic Africa Institute.

The political influence of WDs is seldom a function of the political parties and state institutions that they represent, but rather of their power as ‘Big Men’, they write:

Thanks to the economic resources, (ex-) military networks and political capital that they amassed during the earlier hostilities, WDs are well placed to shape the new post-war order being built, they add, noting that these dynamics have been observed in countries ranging from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (Jean-Pierre Bemba), Rwanda (Paul Kagame) and Liberia (Prince Johnson), to Sierra Leone (Julius Maada Bio), South Sudan (Salva Kiir) and Mozambique (Afonso Dhlakama).

But public faith in democratic institutions remains fragile, research suggests.

Some 68% Africans are not confident that their vote is secret, according to a recent survey published by Afrobarometer.

Some 68% Africans are not confident that their vote is secret, according to a recent survey published by Afrobarometer.

Levels of distrust are notably high in some of the continent’s most established democracies, including Senegal, where 89% of respondents said they were cautious about how they vote 9Kenya – 80%; and South Africa – 68%).

“The vote is supposed to be secret, but increasingly we find that people are scared that authorities might find out how they vote,” said Boniface Dulani, a fieldwork operations manager for Afrobarometer, a partner of the National Endowment for Democracy, which surveyed more than 50 000 people across 34 African countries between late 2016 and late 2018. “We are very confident that our surveys are truly representative of the countries where we do them,” said Dulani.

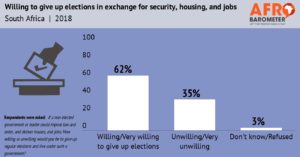

More broadly, the survey reveals the shrinking space for civil and political rights in Africa is shrinking. “We uncover two troubling trends,” the survey states:

More broadly, the survey reveals the shrinking space for civil and political rights in Africa is shrinking. “We uncover two troubling trends,” the survey states:

- First, consistent with the alarms sounded by Freedom House and others, citizens generally recognise that civic and political space is indeed closing as governments’ supply of freedom to citizens decreases. But the results also reveal a decline in popular demand for freedom, in particular the right to associate freely.

- Moreover, we find considerable willingness among citizens to accept government imposition of restrictions on individual freedoms in the name of protecting public security. In a context where violent extremists are perpetrating attacks in a growing number of countries, the public may acquiesce to governments’ increasing circumscription of individual rights and collective freedoms.

“Fear of insecurity, instability, and/or violence may be leading citizens of at least some African countries to conclude that freedoms come with costs as well as benefits, and that there may be such a thing as too much freedom,” it concludes.