Communication has been weaponized, used to provoke, mislead and influence the public in numerous insidious ways, argues Sophia Ignatidou, an academy fellow at Chatham House, researching AI, digital communication and surveillance. Disinformation is just the first stage of an evolving trend of using information to subvert democracy, confuse rival states, define the narrative and control public opinion. Whatever we do, however many fact-checking initiatives we undertake, disinformation shows no sign of abating. It just mutates, she writes for The Guardian:

The next stage in the weaponization of information is the increasing effort to control information flows and therefore public opinion, quite often using – ironically enough – the specter of disinformation as the excuse to do so. Internet shutdowns made headlines recently during India’s communications blackout in Kashmir but they have already become commonplace in Africa. Access Now has reported that internet shutdowns between 2016 and 2018 more than doubled. According to some reports, the app used by protesters in Hong Kong to coordinate, Telegram, also received a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack from mainland China.

The next stage in the weaponization of information is the increasing effort to control information flows and therefore public opinion, quite often using – ironically enough – the specter of disinformation as the excuse to do so. Internet shutdowns made headlines recently during India’s communications blackout in Kashmir but they have already become commonplace in Africa. Access Now has reported that internet shutdowns between 2016 and 2018 more than doubled. According to some reports, the app used by protesters in Hong Kong to coordinate, Telegram, also received a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack from mainland China.

China is also weaponizing information to project its sharp power, analysts suggest.

There is a limit to how much Beijing can export its authoritarianism, but the ruling Communist Party is using its powerful control of communications, traditional media, and social media to project the image it wants the world to share, according to reports.

There is a limit to how much Beijing can export its authoritarianism, but the ruling Communist Party is using its powerful control of communications, traditional media, and social media to project the image it wants the world to share, according to reports.

To quote Christopher Walker, the National Endowment for Democracy’s vice president for studies and analysis: “Rather than reforming, China and any number of other leading repressive regimes have deepened their authoritarianism. And in an era of hyperglobalization, they are turning it outward.”

‘Invasive technification’ has major consequences for individual digital communication between citizens, creating risks not only for users but also for the core domains of democratic nations, above all in the functioning of civic communication as a core component of democratic governance, a recent forum heard.

Technology can no longer be seen as a means for efficiently attaining pre-established ends, but must be seen as a structure which makes new forms of human action and human relationship possible, while limiting the possibilities of others, Gernot Böhme argues in Invasive Technification.

Technology can no longer be seen as a means for efficiently attaining pre-established ends, but must be seen as a structure which makes new forms of human action and human relationship possible, while limiting the possibilities of others, Gernot Böhme argues in Invasive Technification.

Serious action is needed to curb the power of the global tech giants behind the decline in trust in governments and institutions, according to former Digital Transformation Office chief Paul Shetler, the co-founder of AccelerateHQ.

Pre-digital ideologies are obfuscating reality

The rise of platforms like Facebook, Google and Amazon had transformed the world, and governments have so far been unable to address this, he said in the keynote speech at the University of Melbourne’s Disruptions of the Digital: Privacy, Civics, Democracy conference on Friday:

The rise of the gig economy, the encroachment of as-a-service platforms governed by opaque terms of service on traditional forms of property ownership, the lack of trust in governments and corporations and the implementation of smart cities has handed power to big tech companies and taken it away from governments.

“No government in history has had the kinds of powers as tech platforms to govern and police behaviour, yet we still talk about government as the thing we have to be afraid of. Our ideologies don’t really reflect reality. Pre-digital ideologies are obfuscating reality,” he told InnovationAus.com.

“No government in history has had the kinds of powers as tech platforms to govern and police behaviour, yet we still talk about government as the thing we have to be afraid of. Our ideologies don’t really reflect reality. Pre-digital ideologies are obfuscating reality,” he told InnovationAus.com.

“Fake news” was not a term many people used four years ago, but it is now seen as one of the greatest threats to democracy, free debate and the Western order, The Telegraph’s James Carson adds. A recent report from the House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media & Sport Committee described the UK’s current electoral law as “not fit for purpose” and accused the government of ignoring its recommendations for tackling disinformation and fake news.

The current challenge of information or influence operations – including disinformation – is an age-old issue. During the Cold War, the US and Soviet Union both engaged in soft diplomacy in an attempt to influence outcomes across the globe, the Wilson Center reports.

The current challenge of information or influence operations – including disinformation – is an age-old issue. During the Cold War, the US and Soviet Union both engaged in soft diplomacy in an attempt to influence outcomes across the globe, the Wilson Center reports.

Since the expansion of the Internet and development of sophisticated online targeting tools, organized disinformation campaigns as well as homegrown disinformation efforts have impacted elections, caused violence, and presented a serious challenge for policymakers and the major internet platforms, according to a recent forum, moderated by CNN anchor Kate Bolduan (above).

“While a lot of the tactics are the same, the tools have changed. … Social media allows those bad actors [including Russia] to spread those messages much more quickly,” said analyst Nina Jankowicz. “They allow them to travel at lightning speed, and also allows those messages to be targeted to the very people who will find them most appealing. That’s what makes what we’re seeing today so much more difficult to counter.”

“While a lot of the tactics are the same, the tools have changed. … Social media allows those bad actors [including Russia] to spread those messages much more quickly,” said analyst Nina Jankowicz. “They allow them to travel at lightning speed, and also allows those messages to be targeted to the very people who will find them most appealing. That’s what makes what we’re seeing today so much more difficult to counter.”

Technology will lay a vital role in democratic renewal, says billionaire philanthropist Nicolas Berggruen, discussing his book: Renovating Democracy: Governing in the Age of Globalization and Digital Capitalism, with the FT’s John Thornhill.

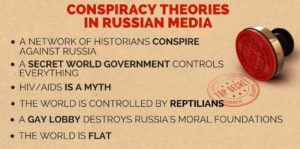

Source: EU vs Disinfo

Both foreign and domestic disinformation are problems in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and awareness of the challenge there is limited, adds Darko Brkan, the founding president of Zašto ne (Why Not), a Sarajevo-based nongovernmental organization that promotes civic activism, government accountability, and the use of digital media in deepening democracy. Research is an important step for developing future action, he writes for the NED’s international Forum’s Power 2.0 blog.

Conspiracies designed solely to delegitimize a political opponent — rather than in service of finding the truth are deeply problematic for democracy, notes Democracy Works.*

Political scientists Russell Muirhead and Nancy Rosenblum call it “ without the theory” and unpack the concept in their book A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy. The new conspiracism is a symptom of a larger epistemic polarization, they contend. When people no longer agree on a shared set of facts, conspiracies run wild and knowledge-producing institutions like the government, universities, and the media are trusted less than ever.

without the theory” and unpack the concept in their book A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy. The new conspiracism is a symptom of a larger epistemic polarization, they contend. When people no longer agree on a shared set of facts, conspiracies run wild and knowledge-producing institutions like the government, universities, and the media are trusted less than ever.

*The blog of the McCourtney Institute for Democracy at Penn State.