China’s rapidly increasing political influencing efforts and the self-confident promotion of its authoritarian ideals present a fundamental challenge to western democracies, analysts Thorsten Benner and Kristin Shi-Kupfer write for The Financial Times:

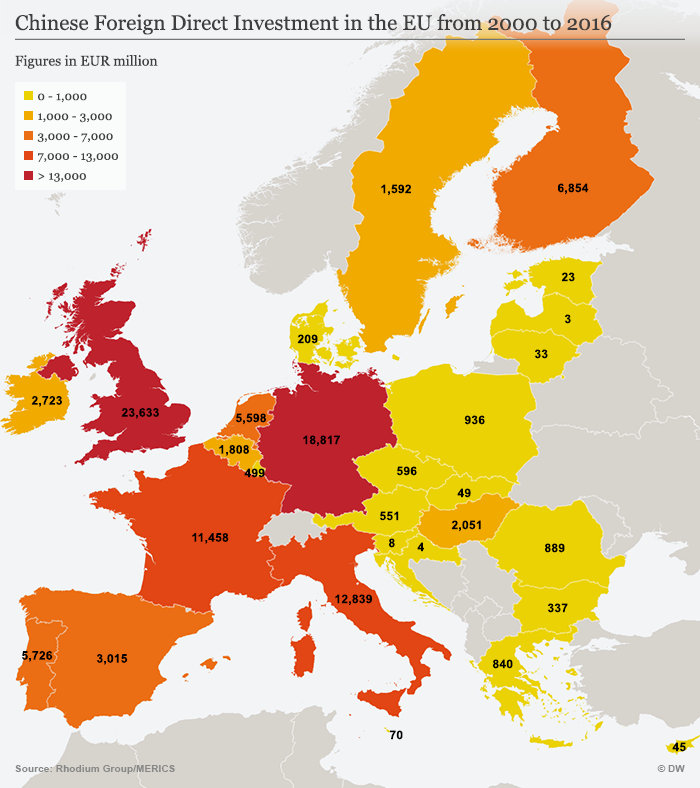

Drawing on its economic strength and a Communist Party of China apparatus that is geared towards strategically building stocks of influence across the globe, Beijing’s efforts are bound to be much more consequential in the medium to long term than those of the Kremlin. Nowhere is the gap between the scale of China’s efforts and public awareness of the problem larger than in Europe. EU member states urgently need to devise a strategy to counter China’s authoritarian advance.

Beijing pursues three related goals, note Benner and Shi-Kupfer, co-authors of “Authoritarian Advance: Responding to China’s increasing political influence in Europe”:

Beijing pursues three related goals, note Benner and Shi-Kupfer, co-authors of “Authoritarian Advance: Responding to China’s increasing political influence in Europe”:

- First, it seeks to weaken western unity within Europe and across the Atlantic. One aim of this is to prevent Europe from challenging China’s human rights record and its hegemonic ambitions in the South and East China seas.

- Second, it aims to build European support on specific issues such as market economy status and a free pass for Chinese investments.

- Third, Beijing pushes hard to create a more positive global perception of China’s political and economic system as a viable alternative to liberal democracies. To further these goals, China commands a comprehensive and flexible influencing toolset in Europe, ranging from the overt to the covert and strategically deployed across three arenas: political and economic elites, media and civil society & academia.

The next US ambassador to Australia has condemned China’s foreign influence operations and told Congress America would rely on Australia to help uphold the international rules-based system in the Asia-Pacific, The Guardian reports:

The next US ambassador to Australia has condemned China’s foreign influence operations and told Congress America would rely on Australia to help uphold the international rules-based system in the Asia-Pacific, The Guardian reports:

In an excoriating assessment of China’s increasingly muscular posture in the region, Harry Harris said Beijing’s “intent is crystal clear” to dominate the South China Sea and that its military might could soon rival American power “across almost every domain”….. “China’s intent is crystal clear. We ignore it at our peril,” he said. “I’m concerned China will now work to undermine the international rules-based order.”

“Australia is one of the keys to a rules-based international order,” Harris said.

To the extent China tries to extend control over inflows of information — including by seeking to curtail critical content in scholarly journals from the West that circulate in Chinese academia — or tries ham-handedly to promote its own narrative in the Western media, it is hurting its own cause, analyst Nathan Gardels writes for The World Post, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post:

As Thomas Kellogg writes, such an effort has already been saddled [in a report from the National Endowment for Democracy] with a pejorative moniker — “sharp power.” Yet, there is an important distinction between China and Russia’s efforts to manipulate public opinion. Russia is trying to sow division and discord in the Western body politic to undermine the democratic discourse; China is clumsily trying to control its own image in the West.

As Thomas Kellogg writes, such an effort has already been saddled [in a report from the National Endowment for Democracy] with a pejorative moniker — “sharp power.” Yet, there is an important distinction between China and Russia’s efforts to manipulate public opinion. Russia is trying to sow division and discord in the Western body politic to undermine the democratic discourse; China is clumsily trying to control its own image in the West.

China has become much more confident in presenting its economic and political model as a “better alternative” to liberal democracy, said Jan Gaspers, head of the European China Policy Unit at the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS).

A MERICS report showed China “creating layers of active support for Chinese interests” by “fostering solid networks among European politicians, business, media, think tanks and universities,” including in Brussels, the heart of European politics, DW adds.

“China’s rapidly increasing political influencing efforts in Europe and the self-confident promotion of its authoritarian ideals pose a significant challenge to liberal democracy as well as Europe’s values and interests,” the report said.

A New Zealand academic who made international waves researching China’s international influence campaigns has linked a number of recent break-ins to her work, reports suggest:

A New Zealand academic who made international waves researching China’s international influence campaigns has linked a number of recent break-ins to her work, reports suggest:

University of Canterbury professor Anne-Marie Brady (left), speaking today from Christchurch to the Australian Parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee in Canberra, outlined three recent events which caused her concern.

“I had a break-in in my office last December. I received a warning letter, this week, that I was about to be attacked. And yesterday I had a break-in at my house,” she said.

“China hasn’t had to pressure New Zealand to accept China’s soft power activities and political influence. The New Zealand government has actively courted it,” Brady found in a recent paper.

To generate soft power, China will likely deploy narratives tailored to the specific perceptions of target audiences, notes Matej Šimalčík, a research fellow at Institute of Asian Studies, an international relations think tank based in Bratislava, Slovakia. This does not mean that any Chinese investment should be rejected as potentially threatening, he writes for the East Asia Forum:

To generate soft power, China will likely deploy narratives tailored to the specific perceptions of target audiences, notes Matej Šimalčík, a research fellow at Institute of Asian Studies, an international relations think tank based in Bratislava, Slovakia. This does not mean that any Chinese investment should be rejected as potentially threatening, he writes for the East Asia Forum:

Turning the Belt and Road Initiative into a security issue would be detrimental, as it would most likely lead to the rejection of projects and investments that could be beneficial for all the parties involved. Nevertheless, both Slovakia and the Czech Republic need to engage in a constructive public debate on the nature and goals of their relationship with China. Media analysis shows that this debate is non-existent in Slovakia and thoroughly politicised in the Czech Republic. Without this debate, two fundamental questions will go unanswered: what are the countries’ respective interests regarding China, and what are the acceptable costs for achieving these goals?

The article was produced as part of the ChinfluenCE project, and with the financial support of the National Endowment for Democracy, the Washington-based democracy assistance group.

The article was produced as part of the ChinfluenCE project, and with the financial support of the National Endowment for Democracy, the Washington-based democracy assistance group.

Jonathan Hillman notes a related conundrum in China’s main foreign policy initiative, Gardels adds:

“An idea as big as China’s ‘Belt and Road’ is bound to have contradictions. As Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy vision, it is massive in all dimensions, aiming to bind Beijing with the rest of the world through more than $1 trillion of new infrastructure, scores of trade agreements and countless other connections,” he writes from Tashkurgan, a Chinese town on the Pakistan border.

“But there is a fundamental tension between the connectivity China says it seeks and the control it is unwilling to give up,” says Hillman, referring to the massive presence of anti-terror security forces and imposing police outposts across Xinjiang’s predominantly Muslim Uyghur towns and cities. “Even as China claims to be championing globalization and broadening ties, it is clamping down in critical borderlands that Belt and Road routes would pass through, potentially crippling its own projects,” concludes Hillman.