Even as some leaders exploit the COVID-19 pandemic, their inability to deal with popular suffering will act against the myth that they and their regimes are impregnable, the Economist observes. In countries where families are hungry, where baton-happy police enforce lockdowns and where cronies’ pickings from the abuse of office dwindle along with the economy, that may eventually cause some regimes to lose control. For the time being, though, the traffic is in the other direction, it adds.

Even as some leaders exploit the COVID-19 pandemic, their inability to deal with popular suffering will act against the myth that they and their regimes are impregnable, the Economist observes. In countries where families are hungry, where baton-happy police enforce lockdowns and where cronies’ pickings from the abuse of office dwindle along with the economy, that may eventually cause some regimes to lose control. For the time being, though, the traffic is in the other direction, it adds.

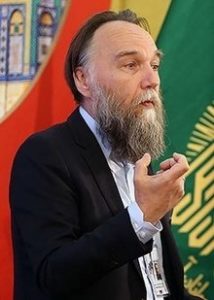

The coronavrus is creating a post-globalist, illiberal and anti-democratic world of slosed societies, according to Russian philosopher Alexsander Dugin. Even if the coronavirus is tamed, there is no going back to globalism, and we have entered a multipolar world where authoritarianism – even in the United States – will set the tone, he contends, according to MEMRI.

Wikipedia: Alexsander Dugin

“From an ideological point of view, … we are experiencing a transition from an open society to a closed one, and the longer this fight will last in conditions of a closed society, and only in such conditions it can be conducted, the deeper the institutions of this post-global order will take root.”

But the idea of a Nationalist (or Populist) International is unlikely survive the coronavirus pandemic as recent months have further teased out the differences between these conflated governments, notes FT analyst Janan Ganesh. Their domestic autocracy is real enough, but their coherence as a bloc is overstated. Liberalism is not confronted by anything like a unified opponent.

No doubt, the momentum has been with authoritarians in recent times. The question is whether they add up to a cohesive front against democracy, he adds.

What does pandemic democracy look like?

Of all political forms, democracy is the most dependent on the participation of its citizens, adds Corey Robin, a professor of political science at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Critically, that participation is supposed to be collective. Citizens are bound to each other, which makes them a people, and they govern as a people, he writes for the NY Review of Books:

Of all political forms, democracy is the most dependent on the participation of its citizens, adds Corey Robin, a professor of political science at Brooklyn College and the CUNY Graduate Center. Critically, that participation is supposed to be collective. Citizens are bound to each other, which makes them a people, and they govern as a people, he writes for the NY Review of Books:

Democracy “is not an alternative to other principles of associated life,” wrote John Dewey. “It is the idea of community life itself.” And though a voting booth may be more reminiscent of a cubicle or a confessional than an assembly, what we do inside of that booth is a public endeavor. Yet, if we cannot gather to assemble or vote, much less deliberate, in what sense can we have a democracy? How do we do politics in a pandemic, self-governance under quarantine? Is it possible to supervise the supervisors if we’re too sequestered—or sick—to vote?

A global pandemic is a political opportunity for leaders to expand state powers and cement authoritarian rule, note analysts Joan Boston, Gabrielle Lim and Brian Friedberg at the Technology and Social Change Research Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center. Crises allow “would-be authoritarians an escape from constitutional shackles,” say political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt.

What’s novel about the pandemic isn’t the authoritarian response. What’s different is the scale and speed with which it’s happening all over the world at the same time. But there are three ways civil society, academia, and fellow journalists can fight this dual-pronged attack on press freedom and democratic participation, they write for Nieman Reports:

What’s novel about the pandemic isn’t the authoritarian response. What’s different is the scale and speed with which it’s happening all over the world at the same time. But there are three ways civil society, academia, and fellow journalists can fight this dual-pronged attack on press freedom and democratic participation, they write for Nieman Reports:

- First, civil society is in a prime position to push back against undue censorship and attacks on the free press. Not only are activists and NGOs connected with issues most salient to the public, but their international networks and connections with intergovernmental bodies can be leveraged to document violations of civil liberties. For example, Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), an organization that promotes grassroots activism and human rights in China, has not only documented and provided analysis regarding Covid-19 and censorship but actively engages with the United Nations.

- Academic freedom and freedom of speech are codependent, making for another point of common cause between academics, researchers, and journalists. In Bangladesh, for example, information controls have expanded to target academics. In Malaysia, the Universities and University College Act 1971 has historically been used to repress academic freedom, … This means not only sharing research with journalists, but taking a position and speaking out when necessary, even on matters that may be politically charged.

- Lastly, international journalism and cross-border reporting can help journalists and press freedom overall. Where local journalists are fearful of government retaliation, foreign outlets and journalists in a different jurisdiction can help. Take Malaysia‘s 1MDB financial scandal, for example…RTWT

Authoritarian regimes such as the Chinese Communist Party are not just cementing their grip on power at home, but also touting their political systems as a model for others to emulate. At the same time, last year also saw robust pro-democracy movements arise around the world—including in Hong Kong, Iran, and Sudan. The current pandemic will impact all these dynamics, the Hudson Institute writes.

Authoritarian regimes such as the Chinese Communist Party are not just cementing their grip on power at home, but also touting their political systems as a model for others to emulate. At the same time, last year also saw robust pro-democracy movements arise around the world—including in Hong Kong, Iran, and Sudan. The current pandemic will impact all these dynamics, the Hudson Institute writes.

Join an online discussion on what the ongoing crisis means for the future of global democracy and what the United States and allies can do to protect freedom around the world.

Tuesday, April 28. 12:00 p.m. to 1:00 p.m. RSVP

Democracy is under attack worldwide by authoritarian bullies like the PRC #in-the-time-of-the-virus @LarryDiamond, @HooverInst ,@FSIStanford, @JoDemocracy , @NEDemocracy tells the @BatchelorShow