With liberalism in crisis, many governments feel free to find their own way of doing things that may have little to do with Western liberal thinking, analysts Vuk Vuksanovic and Marko Savkovic contend.

With liberalism in crisis, many governments feel free to find their own way of doing things that may have little to do with Western liberal thinking, analysts Vuk Vuksanovic and Marko Savkovic contend.

The post-Cold War orthodoxy was that former Soviet satellites like Hungary and post-Yugoslav countries like Serbia should adopt Western liberalism to organize their respective societies and conduct foreign policy. However, the global financial crisis upset the notion that liberal polity knows all the answers, and foreign policy failures like Afghanistan are shattering the concept of liberal international order, they write for the National Interest.

The fundamentals of liberal democracy – “a mixture of civic norms, guaranteed rights, market freedom, social spending and judicious regulation” – are essentially sound, argues Harvard’s Steven Pinker. But insofar as they’re wanting, the balance of these elements should be cautiously tweaked and twiddled through experimentation and empirical feedback, he tells the Guardian.

“Whatever happened to good old liberalism?” asks Pinker, the author of several books, including Enlightenment Now and Rationality, which inspired a current BBC series. “Who’s going to actually step in and defend the idea that incremental improvements fed by knowledge, fed by expanding equality, fed by liberal democracy, are a good thing? Where are the demonstrations, where are the people pumping their fists for liberal democracy? Who’s going to actually say something good about it?”

If liberalism was designed for people ensconced in a labyrinth of institutions, and the citizens of 21st-century democracies are no longer such people, what do we do with it now? the Wall Street Journal’s Barton Swaim asks.

“Liberalism isn’t popular among a lot of younger people, because it was designed to solve a different anthropological problem from the ones we’re facing,” says Jenna Silber Storey, co-author with her husband Benjamin of Why We Are Restless: On the Modern Quest for Contentment. “We were different people when we came up with our liberal institutions to solve the strife of war and persecution.” The political institutions of liberalism, she says, were designed for people who “were already strongly committed to churches, localities, professions and families. But when private lives have broken down—families dissolved, localities less important, religious life absent—liberalism’s framework institutions no longer make sense.”

“Liberalism isn’t popular among a lot of younger people, because it was designed to solve a different anthropological problem from the ones we’re facing,” says Jenna Silber Storey, co-author with her husband Benjamin of Why We Are Restless: On the Modern Quest for Contentment. “We were different people when we came up with our liberal institutions to solve the strife of war and persecution.” The political institutions of liberalism, she says, were designed for people who “were already strongly committed to churches, localities, professions and families. But when private lives have broken down—families dissolved, localities less important, religious life absent—liberalism’s framework institutions no longer make sense.”

They credit the liberal order with a “profound awareness of the manifold and conflicting dimensions of human life and of the consequent challenges of self-government” and hope, Mr. Storey says, “that the liberal institutions that have done so much good for our country can weather the current wave of disorder.”

Maybe the most dangerous effect of the current debate about a crisis, deficit, or malaise of democracy is that these notions, often implicitly, assume that progress, and democratization, are linear, and somewhat automatic. That democracy can only either be ‘achieved’ or ‘in crisis’. This might be a result of the false hope for an end of history that Western intellectuals developed post-1990, the University of Lisbon’s Lea Heyne contends.

But democracy, as illiberalism, is a movement, a process. Only a continuous effort will make sure that the democratic waves remain more powerful than the illiberal waves, and that the real ‘golden age of democracy’ still lies in the future, she writes for the ECPR.

If classical liberalism is so much better than the alternatives, why is it struggling around the world? the Economist asks:

If classical liberalism is so much better than the alternatives, why is it struggling around the world? the Economist asks:

One reason is that populists and progressives feed off each other pathologically. The hatred each camp feels for the other inflames its own supporters—to the benefit of both. Criticizing your own tribe’s excesses seems like treachery. … Aspects of liberalism go against the grain of human nature. It requires you to defend your opponents’ right to speak, even when you know they are wrong.

Economic historian Deirdre McCloskey observed that liberalism is the mother of the 3,000% increase in material abundance that the world has enjoyed over the past 2 1/2 centuries, notes Emily Chamlee-Wright, the president and CEO of the Institute for Humane Studies, and author of Liberal Learning and the Art of Self-Governance.

What, then, is required of us if we are to reconstruct the liberal project of universal human dignity, civil liberties, constraints on political power, toleration, pluralism, and intellectual and economic openness? she asks in Discourse. To reconstruct the liberal project we must name and reassert the liberal sensibility [which] is less about liberal policy reform and more about fortifying liberal cultural norms and intuitions, and a liberal intellectual tradition that supports those norms and intuitions.

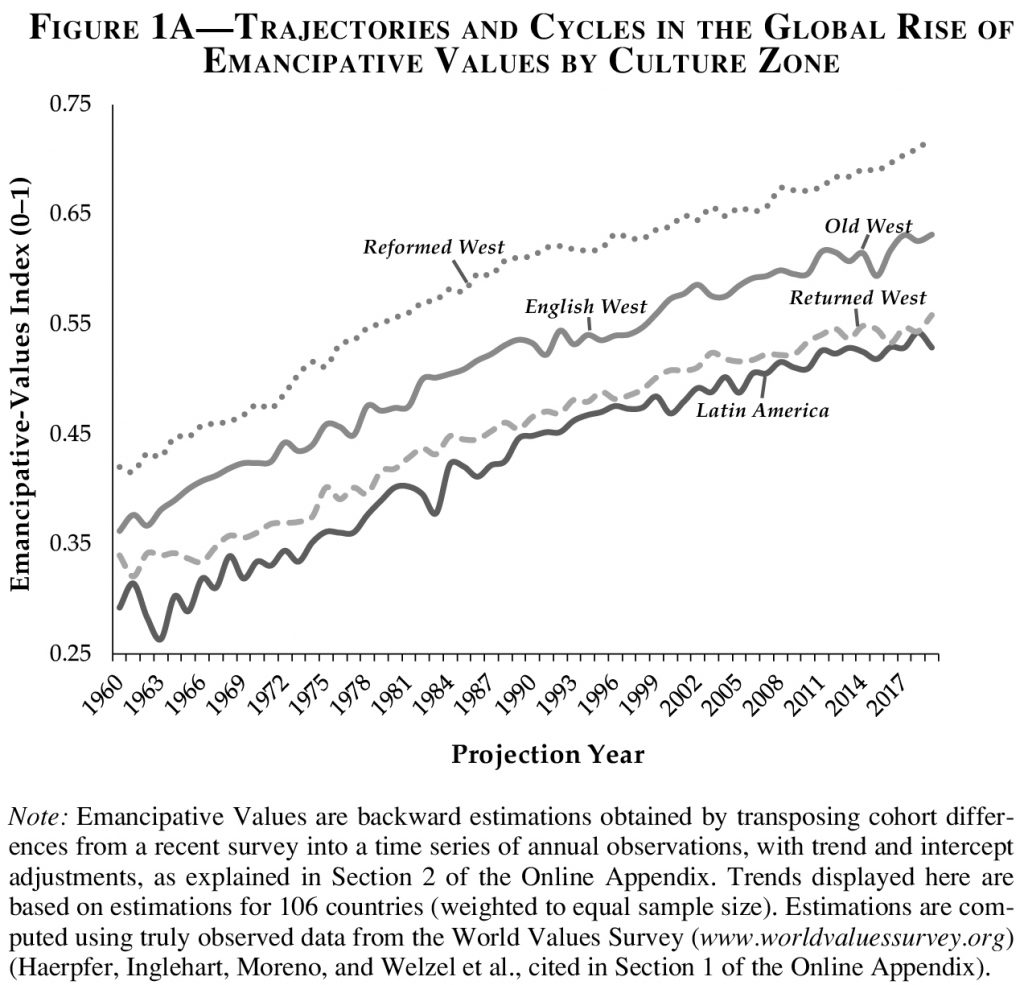

Across the globe, existential opportunities, emancipative values, and liberal democracy have been rising in astonishing unison, promoting a more encompassing trend toward “human empowerment,” adds Christian Welzel, the former president of the World Values Survey Association. Consequently, emancipative values are spreading beyond the borders of Western culture and ascending through generational replacement across all the globe’s culture zones, he writes for the Journal of Democracy.

Illiberal scripts with their authoritarian versions of modernity can slow but not stop the emancipative effects of modernization, Welzel observes. Swings in public mood between liberal and illiberal conceptions of democracy recur in regular cycles on the surface of public opinion, but underneath the turbulence created by those swings the long-term ascendance of emancipative values proceeds – the mightiest antidote against authoritarian redefinitions of democracy. RTWT