Who lost Russia? It’s an old argument, and it misses the point. Russia was never ours to lose. Russians lost trust and confidence in themselves after the Cold War, and only they could remake their state and their economy, argues WILLIAM J. BURNS, the president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former deputy secretary of state.

Who lost Russia? It’s an old argument, and it misses the point. Russia was never ours to lose. Russians lost trust and confidence in themselves after the Cold War, and only they could remake their state and their economy, argues WILLIAM J. BURNS, the president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former deputy secretary of state.

In the 1990s, the country was in the midst of three simultaneous historical transformations, he writes for the Atlantic:

The collapse of Communism and the transition to a market economy and democracy; the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the security it had provided to historically insecure Russia; and the collapse of the Soviet Union itself, and with it an empire built over several centuries. None of that could be resolved in a single generation, let alone a few years. And none of it could be fixed by outsiders; greater American involvement would not have been tolerated.

Before long, the excesses of Putinism began to eat up its successes. Corruption deepened, as Putin sought to lubricate political control and steadily monopolize wealth within his circle. His suspicions of America’s motives also deepened, adds Burns, the author of The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal:

Before long, the excesses of Putinism began to eat up its successes. Corruption deepened, as Putin sought to lubricate political control and steadily monopolize wealth within his circle. His suspicions of America’s motives also deepened, adds Burns, the author of The Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal:

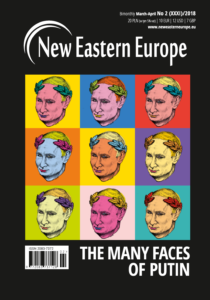

“Uncomfortable personally with political competition and openness, Putin has never been a democratizer,” I wrote in a cable to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, pushing my capacity for understatement to its limits. Democracy promotion was, to him, a Trojan horse, designed to further American geopolitical interests at Russia’s expense and erode the sphere of influence that he viewed as a great-power entitlement. When the Orange Revolution in Ukraine and the Rose Revolution in Georgia ousted pro-Russian leaders, Putin’s neuralgia intensified.

In 2014, the crisis in Ukraine dragged it to new depths, notes Burns, a National Endowment for Democracy board member:

In 2014, the crisis in Ukraine dragged it to new depths, notes Burns, a National Endowment for Democracy board member:

After the pro-Russian president of Ukraine fled during widespread protests, Putin annexed Crimea and invaded the Donbass, in eastern Ukraine. If he couldn’t have a deferential government in Kiev, he wanted to engineer the next best thing: a dysfunctional Ukraine. For a number of years, Putin had challenged the West in places such as Georgia and Ukraine, where Russia had a meaningful stake and a high appetite for risk. In 2016, a year after I left government, he saw an opportunity for a more direct challenge to the West—an attack on the integrity of its democracies.