To understand why liberal democracy is on the defensive, there is no better place to start than the 30th-anniversary edition of the Journal of Democracy, the flagship publication of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), Brookings’ analyst William Galston writes for The Wall Street Journal:

There are external threats to liberal democracy. China’s economic rise has convinced autocrats around the world that their countries can prosper without opening the door to civil liberties and political competition. Russia has effectively used social media to weaken public confidence in democratic elections and boost support for its own brand of conservative authoritarianism.

There are external threats to liberal democracy. China’s economic rise has convinced autocrats around the world that their countries can prosper without opening the door to civil liberties and political competition. Russia has effectively used social media to weaken public confidence in democratic elections and boost support for its own brand of conservative authoritarianism.- But the greatest threats to liberal democracy are internal—the rise of an “illiberal democracy” that erodes protections for individual freedom; an ethnonationalism at war with social diversity; and a loss of confidence among leading democracies that makes their leaders less willing to use political and economic power to create a supportive geopolitical climate for democracy.

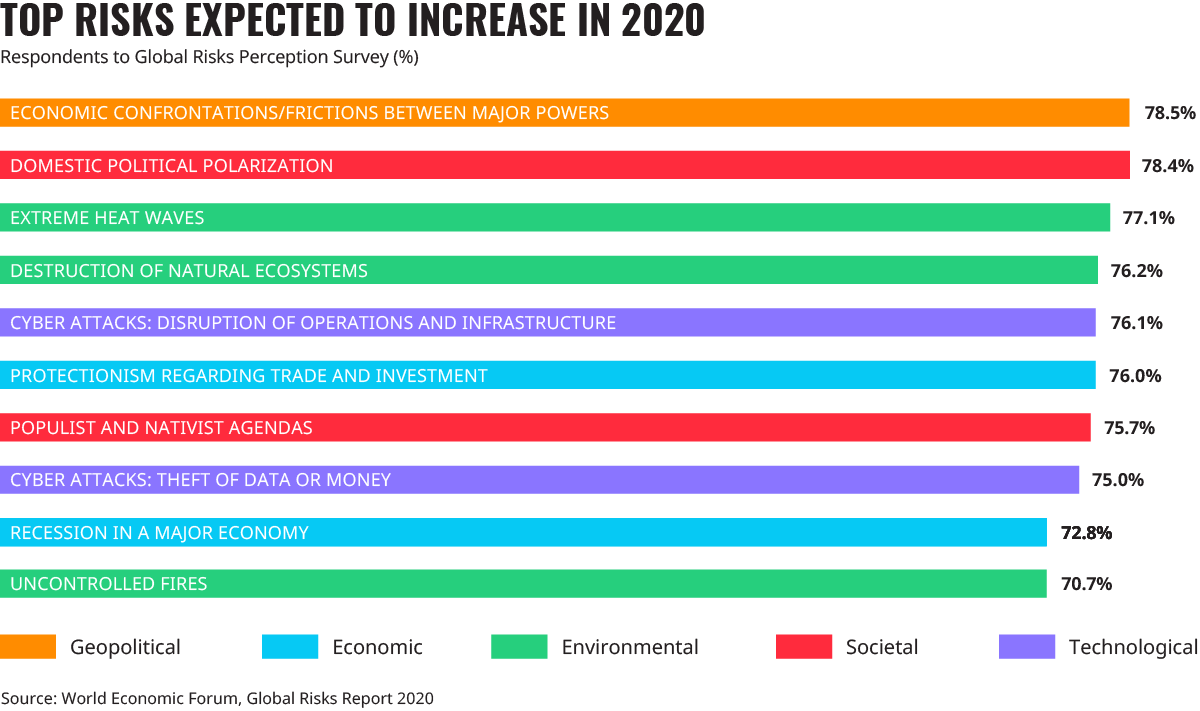

The risks posed by populist and nativist agendas will grow in 2020, say 75.7% of respondents to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Perception Survey (GRPS – see below).

It’s no surprise that growing segments of the middle classes around the world once again turn to illiberal politics, according to David Motadel (@DavidMotadel), a historian at the London School of Economics and Political Science and co-editor of “The Global Bourgeoisie: The Rise of the Middle Classes in the Age of Empire.” In their struggle to preserve their socioeconomic position, parts of the middle classes are turning to protest politics, believing that populist strongmen will protect their interests, he writes for The New York Times:

It’s no surprise that growing segments of the middle classes around the world once again turn to illiberal politics, according to David Motadel (@DavidMotadel), a historian at the London School of Economics and Political Science and co-editor of “The Global Bourgeoisie: The Rise of the Middle Classes in the Age of Empire.” In their struggle to preserve their socioeconomic position, parts of the middle classes are turning to protest politics, believing that populist strongmen will protect their interests, he writes for The New York Times:

The last decade has seen a wide range of shocks: The Great Recession and the neoliberal excesses of our new Gilded Age, which have led to rising inequalities, have squeezed the middle classes almost everywhere. At the same time, some of the old social center feel threatened by social, economic and political demands of previously marginalized groups — minorities, migrants and the poor.

Some of the populist upsurge represents a legitimate democratic response to long-suppressed public concerns. But three aspects of the ethnonationalist-populist turn are dangerous, Galston adds:

- First, populism is by definition anti-elitist, but key liberal democratic institutions inevitably include many people with high levels of education and specialized knowledge. So populist voters scorn institutions in favor of direct relationships with charismatic leaders, who, history suggests, threaten liberal democracy.

- Second, populists believe these leaders should be free to act on their behalf, unrestrained by institutions designed to protect individual liberties and minority rights. Populists typically are hostile to liberal democratic institutions such as constitutional courts, independent agencies and the press—unless populist leaders can bring them to heel.

- Third, ethnonationalists distinguish between the “real” people—defined by descent, ethnicity and religion—and the rest. This contradicts a core principle of liberal democracy—that our shared civic identity as citizens overrides our differences—without which the U.S. could never have thrived as a nation of immigrants.

Ethnonationalism may work in countries with nearly homogenous populations, but it means an ugly politics everywhere else, Galston concludes. If the citizens of diverse societies don’t unite against it, repression and strife are inevitable, and liberal democracy will be in peril.