The labor movement has played a decisively prodemocratic role, not least as a catalyst for democratic transition in such states as Poland, South Africa, Brazil, and Chile, while Tunisia’s UGTT received the Nobel Peace Prize for its role, with other civil society groups, in protecting the country’s fragile democratic process. But has the global democratic regression been facilitated by the weakening of organized labor as a political force? asks Cornell Law School Professor Angela B. Cornell,[1] the coeditor of The Cambridge Handbook of Labor and Democracy.

The labor movement has played a decisively prodemocratic role, not least as a catalyst for democratic transition in such states as Poland, South Africa, Brazil, and Chile, while Tunisia’s UGTT received the Nobel Peace Prize for its role, with other civil society groups, in protecting the country’s fragile democratic process. But has the global democratic regression been facilitated by the weakening of organized labor as a political force? asks Cornell Law School Professor Angela B. Cornell,[1] the coeditor of The Cambridge Handbook of Labor and Democracy.

After three decades of democratic advances in much of the world in the late 20th century, democracy today is under siege in every region of the world. Indeed, it is facing its most significant challenges in over eighty years, with a revival of authoritarian and even fascistic political currents.

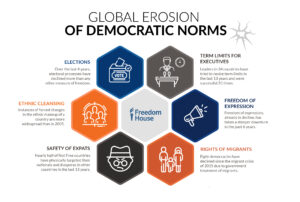

In 2019, Freedom House documented the decline of civil and political rights in both newly established and long-standing democratic regimes, characterizing this dual trend as democracy in retreat. The downward spiral has continued and intensified, with Freedom House this year documenting the global expansion of authoritarian rule in every region of the world. Even in the United States, 64 percent of Americans believe U.S. democracy is “in crisis or at risk of failing,” according to a recent NPR/Ipsos poll.

Freedom House

Democracy’s global retreat has coincided with the erosion of the political strength of labor unions in much of the world. Has democratic regress been facilitated by the weakening of organized labor as a political force? The Cambridge Handbook of Labor and Democracy, released earlier this year, looks at different dimensions of labor’s relationship to democracy, from challenging authoritarian rulers to building democratic regimes, advocating for social and economic rights within democracies, and defending democracy against its adversaries. In a global context of democratic erosion, the book explores whether unions help to safeguard democracy.

The twenty-one chapter volume brings together an interdisciplinary collection of social science and legal scholars providing cross-regional perspectives on labor and democracy in the United States, Europe, Latin America, African and Asia. The chapters build on and update an extensive body of literature that explores the role of organized labor and the working class in the historical construction of democracy, examining a range of more recent cases in non-Western parts of the world. The contributors explore the efforts of labor unions to construct novel forms of social citizenship by deepening or extending democratic practices to broader spheres of social and economic relationships. Additionally, the volume expands the literature in its analysis of recent patterns of democratic erosion, examining its relationship to the political weakening of organized labor, and in several cases, the political alliances forged by workers in contexts of nationalist or populist political mobilization.

A number of chapters highlight the role of the working class in forging democracies, building on a substantial body of literature that demonstrates labor’s pro-democratic force in the historical construction of democracy. The labor movement has played a decisively prodemocratic role. Some of the more emblematic examples of labor movements’ instrumental role in the push for democracy include Poland (with Solidarity), South Africa, Brazil, Chile and Egypt. The Tunisian Labor Union, UGTT, received the Nobel Peace Prize for its leading role, along with other civil society organizations, in preserving the democratic transition.

A number of chapters highlight the role of the working class in forging democracies, building on a substantial body of literature that demonstrates labor’s pro-democratic force in the historical construction of democracy. The labor movement has played a decisively prodemocratic role. Some of the more emblematic examples of labor movements’ instrumental role in the push for democracy include Poland (with Solidarity), South Africa, Brazil, Chile and Egypt. The Tunisian Labor Union, UGTT, received the Nobel Peace Prize for its leading role, along with other civil society organizations, in preserving the democratic transition.

Labor unions also played an important role in displacing colonialism and fighting fascism, fast becoming the target of repression in Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, and Franco’s Spain. Trade unionists around the globe have been the targets of authoritarian regimes, suffering persecution, from both the state as well as business interests. Even in democratic regimes trade unionists have been persecuted by business interests linked to right-wing militias or state actors for their role in advancing the economic and political interests of working people in countries like Guatemala and Colombia. In Colombia between March 2020 and April 2021, 22 trade unionists were murdered.

Labor unions also played an important role in displacing colonialism and fighting fascism, fast becoming the target of repression in Nazi Germany, Mussolini’s Italy, and Franco’s Spain. Trade unionists around the globe have been the targets of authoritarian regimes, suffering persecution, from both the state as well as business interests. Even in democratic regimes trade unionists have been persecuted by business interests linked to right-wing militias or state actors for their role in advancing the economic and political interests of working people in countries like Guatemala and Colombia. In Colombia between March 2020 and April 2021, 22 trade unionists were murdered.

Underlying themes throughout the chapters include class and economic inequality, capitalism and its turn toward neoliberalism, the implications of industrial democracy for workers’ economic and political rights, systemic racism and the intersection between class, racial, ethnic and gender inequalities, the destabilizing impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the working class, and the complex relationship between the erosion of labor rights and democratic institutions.

The year we started this book project, the International Labor Organization celebrated its centennial and the international consensus that fundamental labor rights are essential to social justice and political stability. However, organized labor is under assault in much of the world with steep declines in levels of unionization. The U.S. is a particular outlier among rich democracies with a union density rate of only 10.3% (private sector rate of 6.1%), in sharp distinction to the high union approval rate of 68% in the U.S., according to Gallup poll data. Union support is at its highest level since 1965, the year union density was close to three times the current rate. President Biden’s National Labor Relations Board has more consistently enforced the statute and workers’ rights, but it would take a sustained effort to see much movement in union membership levels.

The year we started this book project, the International Labor Organization celebrated its centennial and the international consensus that fundamental labor rights are essential to social justice and political stability. However, organized labor is under assault in much of the world with steep declines in levels of unionization. The U.S. is a particular outlier among rich democracies with a union density rate of only 10.3% (private sector rate of 6.1%), in sharp distinction to the high union approval rate of 68% in the U.S., according to Gallup poll data. Union support is at its highest level since 1965, the year union density was close to three times the current rate. President Biden’s National Labor Relations Board has more consistently enforced the statute and workers’ rights, but it would take a sustained effort to see much movement in union membership levels.

In addition to the extremely low union density rate, the U.S, like several other countries, has also experienced significant challenges that undermine the strength of its democracy, culminating in an unprecedented effort by the incumbent president to overturn the 2020 election results. Even before that, Freedom House had documented the decline in U.S. ranking on political rights and civil liberties in recent years, asserting that “its democratic institutions have suffered erosion, as reflected in partisan manipulation of the electoral process, bias and dysfunction in the criminal justice system, flawed new policies on immigration and asylum seekers, and growing disparities in wealth, economic opportunity and political influence”.

The high level of poverty and extreme income inequality in the U.S. is among the very worst of wealthy industrialized democratic countries as we return to the levels witnessed in the Gilded Age. This level of inequality erodes social cohesion and undermines democratic institutions. Not only has the weakening of labor since the 1970s coincided with increasing inequality, it is also a period characterized by growing concern about the erosion of the quality of democracy and the distortions of the democratic process by concentrated wealth. The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index likewise shows a decline in the United States.

The high level of poverty and extreme income inequality in the U.S. is among the very worst of wealthy industrialized democratic countries as we return to the levels witnessed in the Gilded Age. This level of inequality erodes social cohesion and undermines democratic institutions. Not only has the weakening of labor since the 1970s coincided with increasing inequality, it is also a period characterized by growing concern about the erosion of the quality of democracy and the distortions of the democratic process by concentrated wealth. The World Justice Project Rule of Law Index likewise shows a decline in the United States.

Empirical research confirms the broad positive impact of union membership on most types of political civic involvement, including voting, protesting, signing petitions, etc. In research based on three nationally representative datasets that address the political behavior of Americans from 1973-1994, union membership positively affected electoral and collective action outcomes, especially for low-income voters. In particular, union membership increases the likelihood of voting in a presidential election by 18% and volunteering for an election campaign by 43%. “Unions arguably play a unique role bringing the voices of the working class individuals into American political life,” the research suggests, and their decline foreshadows “a less democratic future”.

Unions build political power in local communities as well as at the state, national and global levels. At all levels, unions and union federations advance policies that benefit working people and help to counterbalance the role of capital. In the U.S., the labor movement has been “the most prominent and effective voice for economic justice,” according to one account.

Unions build political power in local communities as well as at the state, national and global levels. At all levels, unions and union federations advance policies that benefit working people and help to counterbalance the role of capital. In the U.S., the labor movement has been “the most prominent and effective voice for economic justice,” according to one account.

Substantial research demonstrates that unions reduce inequality, which is important for bolstering democracy. In addition to the wage and benefit enhancement that unionized workers receive, unions have been instrumental in the passage of labor protections and the social safety net, including social security, minimum wage and overtime, workplace health and safety, medical leave, among others, confronting strenuous opposition from business interests. Organized labor was a “critical element” in the successful New Deal programs that benefitted the working class, and it played a key role in the passage of civil rights legislation and the prohibition against housing discrimination.

Right-wing parties and populist leaders in numerous countries around the globe have been able to garner support from the white working class using anti-immigrant rhetoric, xenophobia and white nationalism. Neoliberalism has left the working class struggling and helped to create the discontent that has been the fertile terrain for these very extreme positions.

According to recent scholarship, unions diffuse and reinforce values of solidarity among their members and this can effectively counter the racist and exclusionary ideology of the radical right. Union membership reduces racial resentment toward African Americans, which helps explain why the labor movement is the largest mass membership organization of people of color. There is ideological and strategic incentive for unions to mitigate racial resentment among the rank and file union members in order to advance organizational maintenance and growth.

According to recent scholarship, unions diffuse and reinforce values of solidarity among their members and this can effectively counter the racist and exclusionary ideology of the radical right. Union membership reduces racial resentment toward African Americans, which helps explain why the labor movement is the largest mass membership organization of people of color. There is ideological and strategic incentive for unions to mitigate racial resentment among the rank and file union members in order to advance organizational maintenance and growth.

Workers of different origins and nationalities participate together in unions. This solidarity has a positive impact on the workers. Research on recent elections in Western Europe involving right-wing ethno-nationalist parties concluded that the unionized working and middle class are less likely to vote for the radical right than the non- unionized, even while the radical right expands its vote share among non-unionized workers.

The Solidarity Center, a core partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), supports labor unions worldwide.

Social science research helps to confirm the myriad ways independent trade unions strengthen democracy and resist authoritarian challenges. Whether it is building solidarity among their own members who are less likely to support authoritarian leaders and regimes, unions have unique strengths and are critically important to democratic governance. Now more than ever, we need strong, independent labor unions to bolster democracy here in the United States and around the globe.

[1] Angela B. Cornell is the coeditor of The Cambridge Handbook of Labor and Democracy with Mark Barenberg. She is a Clinical Professor at Cornell Law School where she is the founding director the Labor Law Clinic and teaches labor law.