MEMRI

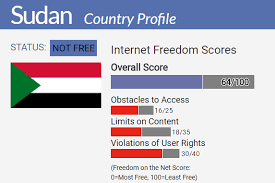

Sudan’s military authorities are shutting down the Internet in an effort to suffocate the current pro-democracy protest movement.

Internet shutdowns are not new, but they have become increasingly popular instrument among dictators and autocrats who want to control their citizenry and preempt political threats, says Steven Feldstein, the holder of the Frank and Bethine Church Chair of Public Affairs and an associate professor at Boise State University.

My research indicates that Internet shutdowns are one item in a broader toolkit of digital repression that includes digital surveillance, online censorship, cyberattacks and hacking, disinformation, and targeted arrests and detentions of Internet users. As more citizens exclusively rely on the Internet to communicate and conduct business, autocratic governments are increasing their efforts to monitor and control cyberspace, he writes for The Post’s Monkey Cage blog.

My research indicates that Internet shutdowns are one item in a broader toolkit of digital repression that includes digital surveillance, online censorship, cyberattacks and hacking, disinformation, and targeted arrests and detentions of Internet users. As more citizens exclusively rely on the Internet to communicate and conduct business, autocratic governments are increasing their efforts to monitor and control cyberspace, he writes for The Post’s Monkey Cage blog.

Given the high cost and dubious impact, why is the Sudanese regime relying on shutting down the Internet? asks Feldstein, a nonresident fellow in Carnegie’s Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program:

- First, the Sudanese regime is desperate. It has few places left to turn to solidify its political survival. Its military junta is already tapping financial spigots from Saudi Arabia and the UAE, but that money won’t last forever. The regime needs to show short-term strength to assure its backers that it is worth supporting. As a result, the junta is willing to sacrifice Sudan’s long-term economic stability for short-term gain. Shutting down the Internet, like heavy violence, is part of a last-ditch strategy to break the protesters’ momentum and buy time for the regime.

Second, comparatively few of Sudan’s citizens use the Internet: only 31 percent of its 40 million citizens have access to it, and only 7 percent of the population use social media. That means shutting down those services doesn’t hurt its economy as much as it would those of more developed economies. Moreover, its most active Internet users overlap heavily with those who are demonstrating. Individuals who will suffer most from a shutdown are the very protesters the regime is trying to quash.

Second, comparatively few of Sudan’s citizens use the Internet: only 31 percent of its 40 million citizens have access to it, and only 7 percent of the population use social media. That means shutting down those services doesn’t hurt its economy as much as it would those of more developed economies. Moreover, its most active Internet users overlap heavily with those who are demonstrating. Individuals who will suffer most from a shutdown are the very protesters the regime is trying to quash.- Third, Sudan’s security state is a victim of what social scientists call “path dependency.” Disrupting the Internet is a tactic it deploys often and knows well. It doesn’t have the right infrastructure to implement more sophisticated instruments of digital repression, and now is too late to shift course. Across the region, it sees many of its peers deploying the same tactics to counter government protests; 22 African countries have recorded Internet shutdowns in the last five years, from Ethiopia and Uganda to Zimbabwe. The Sudanese regime knows it is in good company when it comes to deploying this strategy. Why change? RTWT

In the next few days, there are hopes that pressure from the international community will force the military back to negotiations with civilian groups, reports suggest. Whether another round of talks can yield a legitimate democracy for Sudan is another question, says Amal Madibbo, an associate professor at the University of Calgary. But many are optimistic that new negotiations will occur while curtailing violence.

“This time is different because there is a lot of international pressure on the government to pass it to civilians,” she says. “But it doesn’t guarantee anything because the military is unpredictable.”

Sudanese civil society groups (below), including several partners of the National Endowment for Democracy, have called for a negotiated transition to democracy.