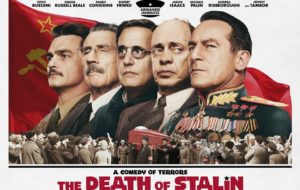

If you want to know what might keep Vladimir Putin from a good night’s sleep after his expected landslide reelection as president of Russia on Sunday, there’s no better place to start than Armando Iannucci’s satirical film, “The Death of Stalin,” notes Stephen Sestanovich, a professor of international diplomacy at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

If you want to know what might keep Vladimir Putin from a good night’s sleep after his expected landslide reelection as president of Russia on Sunday, there’s no better place to start than Armando Iannucci’s satirical film, “The Death of Stalin,” notes Stephen Sestanovich, a professor of international diplomacy at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

“It was banned in Russia for what the minister of culture called ‘insulting mockery of the Soviet past.’ But don’t be misled. If you were president of Russia you’d want this movie banned not for its ideas about Joseph Stalin but for the  ideas it may give people about you. It’s an inventory of Putin’s nightmares as he embarks on a new term,” the former National Endowment for Democracy board member (right) writes for the Washington Post.

ideas it may give people about you. It’s an inventory of Putin’s nightmares as he embarks on a new term,” the former National Endowment for Democracy board member (right) writes for the Washington Post.

The election result, many analysts say, is that as infighting over the country’s domestic course continues at the top, Putin will have an interest in intensifying the conflict with the West, the Post adds.

“This destruction of the systems of governance leads to adventurism abroad,” said Gleb Pavlovsky (left), a former Kremlin adviser turned prominent Putin critic. “That’s why this activity abroad will only intensify.”

“This destruction of the systems of governance leads to adventurism abroad,” said Gleb Pavlovsky (left), a former Kremlin adviser turned prominent Putin critic. “That’s why this activity abroad will only intensify.”

But squaring up to the West only has limited appeal according to political analyst Ekaterina Shulman.

“The besieged fortress mentality is very useful to mobilize the incumbent. It reinforces the idea that there’s no alternative,” she told the BBC. “But it makes the electorate anxious and tired. It wears them out.”

Putin’s predictable election victory has the potential of dividing the European Union and weakening the transatlantic relationship, adds Carnegie analyst Judy Dempsey. Although the EU has, against all the odds, kept rolling over the sanctions on Russia after Putin’s annexation of Crimea four years ago this month, several EU leaders and political parties are, to say the least, ambiguous about Putin, she writes:

From Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán to the UK’s Labour Party opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn to Horst Seehofer, the former leader of Bavaria and now interior minister in Chancellor Angela Merkel’s fourth coalition government—they have all pandered to Putin. Whether through state visits by Putin to Hungary or Orbán to Moscow, or Seehofer rolling out the red carpet for his Hungarian pal in Munich or popping over to see Putin in the Kremlin, and now Italy’s Northern League joining in, Putin has been able to tap into residual pro-Russian sentiment in several EU countries.

Putin still faces numerous political challenges, including what to do about Ukraine and Syria, said Leon Aron, director of Russian studies at the American Enterprise Institute. “Vladimir Putin is not really facing any good choices. It’s balancing one risk against the other.”

The conflict between the government of Ukraine and Russian-backed separatists is somewhat frozen for now, Aron said, even though there are still casualties on both sides. Additionally in Syria, Russia is getting increasingly bogged down, but Putin can’t leave Syrian President Bashar Assad because he promised to restore the government, Aron told PBS.

Sunday’s rigged affair seems on its face a testament to the strength of his regime. But this interpretation papers over a deeper and more fundamental flaw in Putin’s government. While Putin himself has a secure hold on power for the foreseeable future, he will eventually grow old and die. And the government he has created is so dependent on him that no one knows who — or what — will take over when he’s gone, notes Vox analyst Zack Beauchamp:

Sunday’s rigged affair seems on its face a testament to the strength of his regime. But this interpretation papers over a deeper and more fundamental flaw in Putin’s government. While Putin himself has a secure hold on power for the foreseeable future, he will eventually grow old and die. And the government he has created is so dependent on him that no one knows who — or what — will take over when he’s gone, notes Vox analyst Zack Beauchamp:

In March 2017, a scholar named Fiona Hill published a paper on “the question of succession” in modern Russia. At the time, Hill was working at the Brookings Institution, a centrist Washington think tank; today she is in the White House, serving as the National Security Council’s senior director for Russia.

Hill’s paper begins with a stark warning: Putin’s push to centralize power has made the Russian political system remarkably vulnerable if he’s forced out of power or dies in office. “The increased preponderance of power in the Kremlin has created greater risk for the Russian political system now than at any other juncture in recent history,” Hill writes. “Putin has the capacity to designate a successor … but even this could prove a heavy lift for the system.”

“We never quite know what would be a tipping point. As long as the dictator is in place, there is no hope for a country to become a democracy. Once he is out, there is a possibility,” said David Kramer, (second from left), a senior fellow at the McCain Institute and senior fellow in Florida International University’s Václav Havel Program on Human Rights and Diplomacy.

“We never quite know what would be a tipping point. As long as the dictator is in place, there is no hope for a country to become a democracy. Once he is out, there is a possibility,” said David Kramer, (second from left), a senior fellow at the McCain Institute and senior fellow in Florida International University’s Václav Havel Program on Human Rights and Diplomacy.

“It is grossly unfair to say that Putin and Russia are the same. ….. It would be an enormous mistake to cut off the assistance to those in Russia who want democracy,” he told Putincon (right). “We should show solidarity. We can never take democracy and civil rights for granted. Yes, we have our own house to clean in order but there is no pause button to hit. We should stick up with our principle. Putin might be here for 6 years or he might be gone tomorrow,” he added.

Kleptocratic oligarchs

Kleptocratic oligarchs

The UK should target football billionaires such as Roman Abramovich, according to another Russian poisoning victim:

Vladimir Kara-Murza (left), vice chairman of the Open Russia prodemocracy movement, called on Prime Minister Theresa May to act against Putin’s oligarch pals living in the UK. The Chelsea supremo was “one of the closest oligarchs to Putin”, he added. Mr Kara-Murza, who claims he has been twice poisoned in “politically motivated” attacks, also wants action against Uzbek-born billionaire Alisher Usmanov, who owns a big stake in Arsenal.