Yuri Orlov, physicist who became a symbol of Soviet dissent, dies at 96 https://t.co/21j9gD1Mdr

— Democracy Digest (@demdigest) October 1, 2020

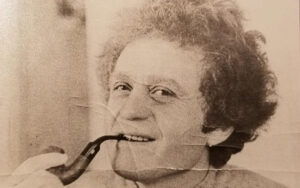

Yuri Orlov Credit: Natan Sharansky

Like his contemporary Andrei Sakharov, a father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb who later won the Nobel Peace Prize, Dr. Orlov was both an eminent physicist and a champion of free speech and human rights. He examined the building blocks of matter, helped launch the Soviet branch of Amnesty International and organized what is widely considered Russia’s oldest human rights organization, the Moscow Helsinki Group.

We lit a fire under the regime, and it was Orlov’s bold vision that made our efforts so effective — and so intolerable from the Soviet point of view, according to his fellow dissident Natan Sharansky.

What he suggested was unprecedented in its boldness, he writes for The Times of Israel: the foundation of an organization dedicated to monitoring the Soviet Union’s compliance with its commitments in the Helsinki Accords, collecting and collating information about human rights violations in the USSR, and passing it to the West via official channels. “We will be stopped, and soon,” he predicted, knowing — as did we all — that the Soviet regime couldn’t afford to let such public acts go on unpunished. “But we might make a difference.”

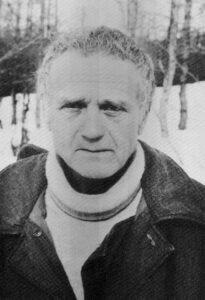

Yuri Orlov in Siberian exile 1984 Credit National Security Archive

“He lived a long and active life, teaching his beloved physics to the last and continuing to stand by the human rights movement,” said the Moscow Helsinki Group, a long-time partner of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

In 1976, Ludmila Alekseeva, recipient of the NED’s 2004 Democracy Award, accepted Orlov’s invitation to join the ranks of the nascent Moscow Helsinki Group where she became the editor and archivist of the group’s documents until Orlov’s arrest.

As far back as 1956, Orlov risked everything to stand up to Soviet totalitarianism, adds He stood up at a party meeting and, in discussing Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of the cult of personality surrounding the late Josef Stalin, called for “democracy based on socialism.” This was enough to get him fired from his government job and expelled from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He was exiled to an institute in Armenia, where he became a world-recognized expert on particle acceleration. He returned to Moscow in 1972, he writes for Esquire.

In 1986, Orlov was traded to the United States along with the jailed journalist Nicholas Daniloff in exchange for the release of Gennady Zakharov, a physicist working in the Soviet UN Mission arrested for espionage. Orlov spent the rest of his life in the U.S., where he was naturalized in 1993, though Mikhail Gorbachev restored his Soviet citizenship in 1990, Meduza adds.

Dr. Orlov came to prominence in the 1970s, at a time when the Soviet protest movement “was hopeless and desperate,” said Lev Ponomarev, a fellow Soviet-era physicist and dissident who now leads the For Human Rights movement. “Any attempts by young people to unite in protest groups were monitored and defeated, and people went to the camps without achieving a noticeable result,” he told The Post.

The U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights & Labor said Orlov was also the first to be awarded the American Physical Society’s Andrei Sakharov Prize, bestowed on scientists for exceptional work in promoting human rights, in 2005.

Yuri Orlov and Ronald Reagan (with interpreter) in the Oval Office, October 7, 1986. Credit Reagan Presidential Library.